ALEX BOWLING

“We decided: lets form a Housing Co-operative! So one evening in the kitchen we put some ideas together”

Alex Bowling: I came to this area in 1973; actually I was just travelling through. I landed at Heathrow and was picked up by this guy Stanley who met me at Heathrow. I had met him the previous year when he came to New York where I was living at the time. He said come through London and you can go to Yugoslavia to see your friends there, so I landed sometime in July, one morning – he was a taxi driver and drove me saying were gonna go down to Queensway and have lunch and we’ll meet a whole bunch of people. We got out of the taxi and the first person I met was Anna Malcolm. Anna was I don’t know how old – Corann (Anna’s Daughter) was one year old and they had just come back from swimming at the Porchester Baths. I liked the woman instantly – I had an immediate rapport with her – she was incredible. I didn’t think much of it and we went off to have lunch and met some other people – friends of my mum and dads’ and he put me on the train to Yugoslavia – the express from Liverpool Street later that evening. I had a Guyanese passport and I landed in Ostend and I was immediately put on the next ferry back to England because I didn’t have visas – when I was in New York I was told I didn’t need Visas because I was in transit – it was a huge problem. I spent the whole week just getting visas and getting to know people in this area and I absolutely fell in love with the place. It was all derelict – there was a lot of it boarded up.

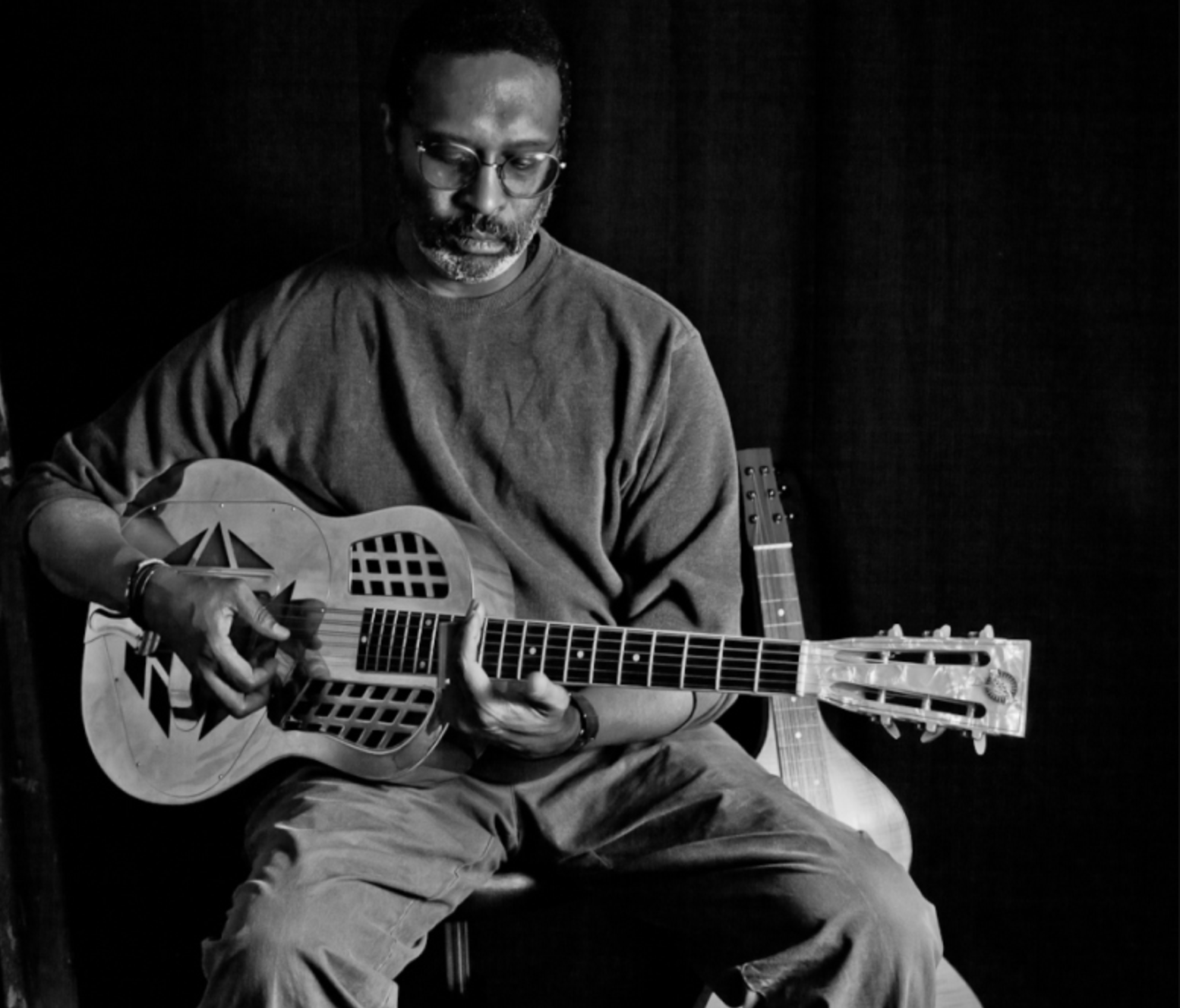

There was a lot of it falling down, still bomb-damaged buildings, but the people were incredible, there was such and amazing community spirit, black people and white people living together with no problems like I had experienced when I was growing up in new York. I got to meet Anna a bit more – not much but we registered in each other’s minds. I got my Visas and went back to Yugoslavia and had an awful time. I came straight back and met up with my best friend who had got me there in the first place – he was from Croatia. We fell out even though we were best friends and it was a horrible situation, a loss of innocence, I woke up to the realities of the world. Going through Germany on the trains there was such heavy security because of the Baader Meinhoff thing. It was heavy going through Europe Although I saw Europe, I didn’t too; you don’t get much on a train, just slices of life. So I came back depressed, having had a horrible time and landed here and I thought OK what can I do? I’ve got time – supposed to be going back to College in New York but didn’t want to I hated it and hated living in the States as well, Vietnam was happening and people were still having problems with rioting and all sorts of political problems. I decided to lengthen my stay and I stayed for six months and managed to find work as a photographer’s assistant. He taught me how to print – it’s the first thing you do. And I thought this is exactly what I wanted to do – it was my life – photography! Then my Visa ran out, it had been six months and I thought I had to go back to New York and I went back depressed because I loved England so much, loved London, loved W11 son much. I had such a great time with wonderful people but I had to leave. So I went back and I started working at my old job, I didn’t go back to college. I worked at a bookshop in Manhattan. They wanted me to stay, they were going to fast-track me into managerial if I wanted. I thought about it – England was in the back of my mind and all I could think about was trying to get back here. The guy I was working for said OK I’ll pay for the ticket and take care of things if you decide to come back. So I said yes and packed up my gear, said goodbye to my mum and came back again a year later. In the meantime I had bought ‘Blondie’ – my Stratocaster. I bought her in a pawnshop for just fewer than two hundred dollars and it’s the most amazing guitar in the world. Loved it and still got it.

I came back, guitar in tow and went back to work with the guy, printing. I got to know Anna Malcolm a bit more and got into a relationship with a woman that didn’t last too long. I was having a great time in the area, which was still run down; up as far as Notting Hill Gate and Holland Park was all derelict, it was incredible but still such an amazing area. Jimi Hendrix! He lived and died in this area – it was one of the things that helped me feel the vibe of the area, here was still a hippy thing going on and we starred to have the three-day week and by then I’d started a relationship with Anna Malcolm and we thought OK what are we gonna do – it was around 1976, I cant live with her, she’s a single mother with two kids and I don’t earn enough to keep them and I’m squatting somewhere locally but before then I was sleeping on the studio floor where I was working but each night I was coming back to the area as the studio was in Barnes. I’d come back to people I knew and got to know Anna and her kids v-better and she decided there were too many people we knew who were homeless or squatting or sleeping on other peoples couches. We decided – lets form a housing co-operative so one evening in her kitchen we put some ideas together. My West Indian Uncle Stan was with us the time we were talking about it. He was gonna be involved in it, single men couldn’t find places cheaply and there were so many people in that situation. Notting Hill Housing Trust did not house men. Councils didn’t either – you’d put your name down on a list and you knew nothing was going to happen for you, the only thing was private landlords, squatting or other peoples couches.

I came back, guitar in tow and went back to work with the guy, printing. I got to know Anna Malcolm a bit more and got into a relationship with a woman that didn’t last too long. I was having a great time in the area, which was still run down; up as far as Notting Hill Gate and Holland Park was all derelict, it was incredible but still such an amazing area. Jimi Hendrix! He lived and died in this area – it was one of the things that helped me feel the vibe of the area, here was still a hippy thing going on and we starred to have the three-day week and by then I’d started a relationship with Anna Malcolm and we thought OK what are we gonna do – it was around 1976, I cant live with her, she’s a single mother with two kids and I don’t earn enough to keep them and I’m squatting somewhere locally but before then I was sleeping on the studio floor where I was working but each night I was coming back to the area as the studio was in Barnes. I’d come back to people I knew and got to know Anna and her kids v-better and she decided there were too many people we knew who were homeless or squatting or sleeping on other peoples couches. We decided – lets form a housing co-operative so one evening in her kitchen we put some ideas together. My West Indian Uncle Stan was with us the time we were talking about it. He was gonna be involved in it, single men couldn’t find places cheaply and there were so many people in that situation. Notting Hill Housing Trust did not house men. Councils didn’t either – you’d put your name down on a list and you knew nothing was going to happen for you, the only thing was private landlords, squatting or other peoples couches.

Slowly we got people involved and we approached the housing Trust as they had loads of empty properties. They were quite happy to help us because Co-operatives were a big feature of London life, especially in areas like this, which didn’t have anything else, where people couldn’t afford anything else. It was decided that we’d work with the housing trust – they’d give us the properties, they would do them up, we would occupy them and wed have an agreement whereby we’d pay the rent and they’d give back to us in maintenance grants or management grants – exactly the way the Co-op operates today we got more people involved and registered with the Housing Associations and as a charity. It snowballed and we got more members and more houses. We didn’t have a limit to number of members or houses at the time. Number 30 was the first house and I wasn’t meant to be living here because there was Emily who lived on the ground floor, Rod and Marie on the top floor and this floor that I am living on was meant for an old Dutch woman who would have been a companion for Emily as they were both similar ages. She was an amazing woman – she was an Old Dutch communist freedom fighter who had had to leave home during the War and wound up living in England she used to tell me all sorts of stories about the things she went through. She was offered a place with better facilities for an older person and she decided to take that offer. I was next on the list and I was meant to be moving into the same house as Anna but on the floor above, she would have the ground floor and basement (at number 32, Lancaster Road) and I’d have the first floor as the Dutch woman moved out of Number 30.

So I moved in here in ’78, when I was 26 or 27 and it was one of the best things that ever happened to me, acquiring my own space! I had no money and couldn’t afford anything. I was given a beat up old fridge and beat up old stove and I bought on Portobello a big foam thing that was my mattress with a sleeping bag that I had brought over from the States and went all over Europe with me. That was it – that was all I had, I had nothing, this place use to resonate and echo because it was so empty and it’s so full now! Oh God! I look at it and think I must get rid of stuff. It used to be neat – I used to be neat, but the more stuff I acquired…

We have very few minimalists in the Co-op! But were not Northern Europeans anyway. I’m the only person in the house from the beginning and I’m still here

There was Anna and myself, Geof Branch a little later and Angie Tieger who was around for the beginning. I am not sure how Ninon and James became involved. There were loads of people but most of them aren’t around anymore. Some people from the Law Centre on Golborne Road became involved also.

Steve Mepsted: It’s testament to the characters the dynamic energy and drive of the ‘early settlers’ as it were, of the Co-op – many who had no experience of housing or housing law or who you had to talk to and say hey, lets make a co-op! But thirty-five years later…still here, it’s quite incredible.

AB: Well no one wanted to live in the area! It was so run down. Like so many parts of London that are run down now and people want to get out of. There was a youth in the area, there was energy, Portobello Road was a focus, and everybody came down on Friday and Saturday, did shopping and met up with each other. There are still things existing today out there and still places you walk past and a memory will hit you.

SM: And that’s rapidly changing

AB: Yea, the Indian shops, where they sell fabrics, you know they were there from the 60’s selling cheesecloth to hippies. The Anglo-Yugoslav Café has gone – mind you there’s no more Yugoslavia!

SM: A famous ‘Times’ article labeled the area and ‘Avernus’ meaning ‘Mouth of Hell’, it prompted a lot of social change in the area as it was swamped with disease from the potteries and the piggeries that thrived here. There were open sewers, the size of a lake, up on Latimer and Avondale Park is the site of what used to be called ‘The Ocean’ – an expanse of stinking water which laid in the holes cut for making bricks form the good clay soil. There was not much agriculture happening as the soil was not good for growing. Pigs were kept for eating.

AB: A psychic woman once flew over the area and said there’s a blue haze of psychic energy about the place, which attracts a certain kind of person. Artistic and not of the mainstream – slightly ‘off’ – not nutty, but not conventional either. One of the things that interested me about the area was the fact that you hard Lordships living right next to people with a million kids – in New York you had segregated areas, a mini-apartheid from the 30’s and 40’s, and way back. Areas where there was gathered a ‘type’. I lived in a Jewish neighborhood but I lived in the black section of that. It wasn’t something I was unhappy with, I didn’t know any better, but when I cam to live here and I saw how people lived together I just thought wow, this is incredible and I don’t know if other areas were like this but I landed here and thought it was amazing – all these old houses and histories. My father was here in ‘58 during the riots, he was here during the war – you would talk to people who had buckets out when it rained, the ceiling would be falling down, the walls would be green with mould – there was unbelievable poverty but it was still an amazing area where people had a feeling for each other, they looked after each other, they cared.

The changes happened when the violence came, mainly the Frontline – the ‘mouth of hell’ you mention maybe, drugs and prostitution, muggings and all sorts of stuff, people were afraid to come into the area, the police were constantly on raids. People would only come in for dugs and would lose their wristwatches instead of getting them.

SM: There was the ‘Dustbin-Lid Hash’ which was clipped dustbin lid, sold off.

AB: Yea, or the ‘Oregano Marijuana’ I remember all that!

SM: Well the ‘Frontline’ has changed – you are more likely to see Madonna walking up it now.

AB: The area changed for the worse. It had to change but it did so in a way that killed the character. They got rid of a lot of the people who lived here – moved them out with the excuse that the house was falling down and we have to sell it and they moved people out and they never came back. With them went a lot of character and characters and interesting stuff, ethnic vibes – lots of people from all over – a lot have gone. And now there’s almost a monoculture. I call it ethnic cleansing. The working class, cheap houses people could by a house for almost nothing and if you had the money, which most people around here didn’t, have you could move in. So you get one family in an entire house, which is funnily enough originally what the houses were built for. This house, number 30 was built in 1895 and it was built for a single family but almost instantly became bedsits.

SM: So when the Trust gave the Co-op some unloved property there must have been a few new skills to be learned?

AB: We had to learn how to manage the Co-op and it was all trial and error, we made a lot of mistakes but we were helped by the trust who had someone who was a liaison person who came to all our meetings, we got to know them very well, and they basically got us through it. They were committed, far more committed than they are now to their neighborhoods. I remember a woman called Shelley who used to come to all our meetings, we got to know her and would go for drinks afterwards and you know, the Trust cared, they didn’t want to see us fail. We had to learn a process and do things properly but a lot of people had that experience from doing other things, being politically motivated for instance, in organisations so they knew how to run meetings, they knew how to elect members, how to lobby to help us run. We had the right people involved. We had very intelligent people but we had to do things properly and we didn’t want the kind of problems that might mean we had the houses taken away from us. This meant we had to have people who were committed, mostly single people, obviously some families, some kids. But we didn’t have too many families; it was a matter of trying to get single people houses.

AB: We had to learn how to manage the Co-op and it was all trial and error, we made a lot of mistakes but we were helped by the trust who had someone who was a liaison person who came to all our meetings, we got to know them very well, and they basically got us through it. They were committed, far more committed than they are now to their neighborhoods. I remember a woman called Shelley who used to come to all our meetings, we got to know her and would go for drinks afterwards and you know, the Trust cared, they didn’t want to see us fail. We had to learn a process and do things properly but a lot of people had that experience from doing other things, being politically motivated for instance, in organisations so they knew how to run meetings, they knew how to elect members, how to lobby to help us run. We had the right people involved. We had very intelligent people but we had to do things properly and we didn’t want the kind of problems that might mean we had the houses taken away from us. This meant we had to have people who were committed, mostly single people, obviously some families, some kids. But we didn’t have too many families; it was a matter of trying to get single people houses.

SM: Because that was the need? A lot of single fathers were around then.

AB: Yes no matter what your energies you cant live like that forever, most people we knew didn’t have any money, there was this housing around but cheap housing was sought after. These were good houses, solid ones not tiny little council ones. I’d been sleeping on floors, squatting and its not always pleasant because you are never sure. Fortunately squats weren’t so looked down upon as they are now – it was allowed as people realized that the housing stock just wasn’t there. You could get a license to squat. There were a lot of workers and shop co-ops that were thriving – like ‘Portobello Wholefoods’ started up that way and there were others like ‘Ceres’ so it was not unusual for this area. I think Islington had a few as well and here were a few in South London, but it definitely worked in this area.

SM: In terms of Housing Co-ops we have and had a few round here. We had Seagull Co-op, Portobello Co-op…

AB: Yes – they based their operations on us but their members wholly own them.

SM: So thirty-five years later West Eleven Housing Co-op is still here! What’s been the secret of its success?

AB: I think it’s down to the people show ran the co-op. we had some real leaders but tone of the problems we are having right now is that we are not getting enough young people in. People move in and you never see them again, ever and that’s unfortunate because its an aging co-op which is one of the problems we are going to have within the next ten, twenty years – what’s going to happen to these older people, I’m one of them! I’m 60 next year…what’s going to happen to me? And will the Co-op survive once the original members are no longer around to run things?

SM: Yes, the secret of the success of the Co-op is partly down to the original members who are still around and still have a lot of energy for the Co-op but because they are getting older the Co-op might crash?

AB: Yea, we had very good people in the beginning, we had committed, political people because it’s a very left wing idea, a co-op and coming out of the 60’s and 70’s where the status quo was were not going to hand you anything you have to go and fight for it. The equality movements of that period were important, sex equality gay equality and racial quality came out of the period and somehow worked its way into the thinking of the co-op. But people don’t know the battles that were fought to get certain things and because of that they have it easier, they expect maybe to just get handed a flat and that they don’t have to be involved, but saying that we still do have quite a few young people who turn up to meetings and do things for the co-op and have a voice.

SM: I raised a point at the last meeting that un housed members – younger members in many cases, could form their own committee to give them a voice and perhaps some interesting ideas could come out of that. It would allow them to accrue points for housing too. After all they are going to be the people who eventually manage the co-op

AB: Yes and one of the other dangers is that of course we don’t own these properties and the Trust might decide that these houses are way too valuable for us to be paying this minimum rent and say well, were going to have to sell the house from under you. I know a lot of people who ended up in Croydon or Shepherds Bush or Hammersmith and it had come close with one of our properties at Number 2 and we fought hard and showed that we are not going to let it happen. We’ve also come close to folding a couple of times with the political battles that go on in the Co-op and people saying to hell with it, let the Trust have it back. The difference for us is that we know who we are going to put into the houses. If they turn up at meetings, we see them, we have some kind of idea of what they’re thinking, we know that if we put them into a house were less likely to have problems with them.

SM: Yes there has to be a lot of commitment to get housed, its not just ‘turn up once and get housed a week later’. I waited and worked 8 years before being housed, others for longer.

AB: At one point a person from every house had to be on the allocations committee, if a person was to move into your house then somebody form that house had to be on it. So that person could have an input, but that’s gone now and we may not really know who is coming in.

SM: So what do you think of this Big Society idea from Cameron?

AB: Oh, don’t make me puke! It existed way before he came up with the idea! People have always been involved; while it may be the same people you are not going to get any extra by making a policy. That’s just their way of getting out of Government. And of course Cameron lives in the area. And to show how ‘in-touch’ he is he leaves his bike unchained outside of Tesco and wonders why it got nicked!

I read the other day, about the Welfare State, The NHS, the University Systems that were brought in after the war, because of the sacrifices that the guys made, their wives and their children, they were not coming back to the same old Britain and now they’re trying to roll back those things to the came old Britain. We’ve got toffs ruling the country and all the things that we’re now beginning to lose because we have taken them for granted; we’re going to have to fight for again. Fight for all these things that I fortunately came into, if I was living in the States now I wouldn’t be entitled to free health care and you don’t want to lose these things, you don’t want to lose cheap housing, they want to take it away. The idea that if an area is upmarket and has social housing within it, then those people should pay the upmarket rents!! Luckily that didn’t happen, who says an area is upmarket? When did it become upmarket?

SM: So we have this little enclave here called the co-op and there’s a couple of other enclaves around but outside of this and outside of the housing trust and council housing its very much about affording private housing – some people are lucky enough to have grown up in the area and still have their homes from when their parents had it.

AB: I’m sure that if they wanted to get rid of us they could do so. It’s happened with the Golborne Estate. We’re an attractive proposition, our houses are not run down, they are well maintained and people want to take pictures of them and stick them on their websites – I’ve been to London and look what I saw. But I don’t think they can close us down too easily, not without a fight, which they know we’ll give.

SM: And they know that we have the skills and knowledge built up over the years, to fight them

AB: Yes, but as we’ve been discussing, will those skills be there in another ten years?

SM: Good point, perhaps the trust knows this as well and it’s a waiting game. But were talking perhaps negatively about the Trust and about the future and threats to the co-op how about expansion, do you think rather than sitting still, we need to invest in more housing and petition for more?

AB: You can’t do it in this area, you’d have to go to Shepherds Bush or Hammersmith and still be the ‘West Eleven Housing Co-op’. We were offered a place near All Saints Church and a property in All Saints Road. But it fizzled out. Slowly the Trust started to run out of property round here although we still had the Sesame Housing group, which was Short-life Housing that we could have kept going. Unless the area suddenly takes a nosedive with house prices and people decide to move out. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the Trust is going to buy the property and give it to us to run. I hope the Co-op keeps going after I’m long gone and that younger people fond a commitment to the co-op in a way that they haven’t necessarily for the last ten years or so. People need to be in place to take over from the others who don’t want to run things anymore. You know, people get tired of it, if they are the same people doing everything. We need people who are going to be into a co-operative spirit and not thinking, oh I’m gonna be housed! We could so lose everything as a co-op as we don’t own the buildings. This is one of the best things that has happened to me in my life and if it wasn’t for Anna Malcolm and her idea, because I never would have thought of it, I wasn’t experienced enough to know about that stuff and didn’t know the right people either. She had an amazing energy and a lot of us owe her a great deal. It’s allowed me to stay in one of the greatest neighbourhoods on the planet!