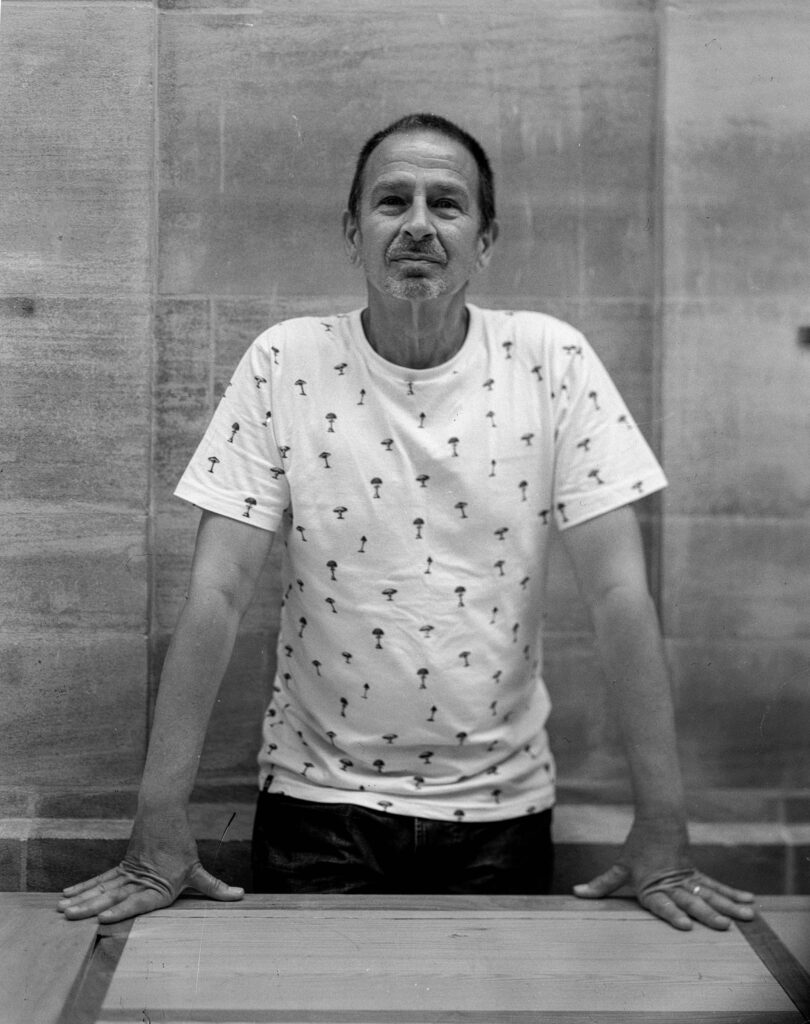

Mike Webber photographed at Southwark Cathedral

I met with Mike Webber, an archaeologist who specialises in the archaeology of the River Thames. Sun 17th October 2021, Southwark Cathedral.

Each person has a different way of looking at the river, and all of these conversations add to my knowledge and help me to understand my own feelings about it.

How did you inherit the River?

My first memories of the River were visits with my Dad. We lived in North London, and I have these memories of us taking the 43 to the City and looking down at the River from London Bridge. My father told me how important it was in the past, and how many ships you would see. He told me how he as a child would come down just to look at the various types of ships from all over the world. He mentioned it quite a lot and it was clear to me that the river was something important in my Dad’s time.

When I got my first children’s bus pass, the ‘Red Rover’, I got a bus across London Bridge and explored Bankside which was very different then, it was full of derelict warehouses and bushes everywhere and lots of ivy, it was pretty much a derelict industrial landscape, which was very exciting! The area along Clink Street was dark and there were overhead walkways from the warehouses on the edge of the river to the warehouses behind, I remember that as very spooky. Then I lost touch with it really, as I grew up and became a teenager, the river became a barrier and I didn’t go South; South London was a different place to North London. I didn’t think about Southwark or Peckham or Brixton – it was all just ‘South of the River’ and it was somewhere as a North Londoner I just didn’t go until very much later.

I’d been away from the river and just didn’t really figure it in my life until I’d been an archaeologist for a while working at The Museum of London. I had a job labelling finds which is a very tedious thing to do, in a portacabin on the site of what is now St. Paul’s Boys School overlooking Bankside Power Station, and one lunchtime I looked over the wall and saw people on the beach so I wandered down. I was hugely surprised that the animal bone and pottery that I was writing tiny numbers on in my portacabin, could just be picked up from the beach and also how different the sound is when you are down there. It was the perfect place to go at lunchtime to relax and get my head together but also, I realised that I could find the things that the experts who were overseeing my work were teaching me about. So, I could take examples of various bits of pottery home. From that moment on the river became something quite special. It was a place I could go to chill out but also a place where I could learn and take pieces of the past away with me. That’s where it all started really.

Years later someone asked me if I’d be interested in doing an archaeological survey of the Thames, which I jumped at. Remembering my father, he would have been so proud that I was an archaeologist working on the Thames, it was a great honour. He died just before that time. So then I was working all up and down the river and got to know just how different it is in different places, I got to see it in the Summer and Winter. We worked with the Environment Agency, with people who had so much knowledge and were willing to share it. It was through them that I got to understand the river as an environmental resource, realising how alive it is despite the pollution and the sewage. So, I really started to feel a bond with the river and as well as working on it I started to visit even more on my days off. Not to go mudlarking or do archaeology but just to convene with the nature of it; this really powerful force. Growing up in London all my life and later in Central London I didn’t have the daily chance to be around real nature and even going out to Epping Forest one experiences a very gentle nature, whereas the river is really quite dangerous, it has a dark side; something like thirty people a year are fished out of the Thames; some through accidents but unfortunately an awful lot through suicide. But despite this dark side the river is still where I go to get some space and experience some sort of spirituality.

Through my archaeology work I realised that people had been using the river as a spiritual space since they very first populated the London area. Even Christians; there’s evidence that when people came back from pilgrimage they would throw their pilgrim badges into the river, maybe to thank the Lord for a safe journey. People today may not think of this as a ritual activity; but I often see people throwing coins into the water.

Another very important period in my relationship with the river was after I finished the survey I was asked if I was interested in taking children down to the foreshore, to learn about history and archaeology, the thought of which I found very scary! But thanks to Ali Taylor of Thames Explorer Trust, who was really my mentor, I discovered the educational possibilities of the river – not just archeology and heritage but also wildlife. It became about giving children a sense of their place in the world and more specifically in London. What better way for children to learn about history and find their own place in it than actually picking up their own pieces of the past. Although I’d explain to them what period the object came from and what it might have been used for, I realised that they immediately had their own ideas and would come up with wonderful stories. One child I remember really well. I was speaking to her teacher about what they were studying at school and was there anything I could link in with. She said they were doing Haikus, well my education was Haiku free! So, I had to go home and look up what a Haiku was. So, what we did was ask the children to write a Haiku which began “I am the River Thames” and it brought tears to my eyes when I read this one Haiku.

I am the River Thames

Lots of fish live in me

It tickles

The thing about teaching children is they will see the world in unexpected and different ways, so while I was teaching, I was learning so much from them about different ways to look at the river and to interpret the past.

What is it that keeps bringing you to the river?

Personally, it’s the place where I can feel at peace . I’m not a religious person but there is something about the river that speaks to that. Another thing I love about the river is the churches along it. People are christened there, married there, have their funerals there. Churches in my mind have absorbed every human emotion; the real extremes of celebration; birth and marriage, but also death and grief. And that to me makes them very special spaces. The same thing is true of the river, it’s been so many things to so many people. Quite clearly, from archaeological evidence of the very first people who came to the area, we find strong evidence of a relationship with the river. In this patch of the river, right in front of Southwark Cathedral, a friend of mine found a Mesolithic tranchet axe, more than 10,000 years old. These are commonly known as ‘Thames picks’ because so many have been found in the River. They are very rarely found on dry land sites, you get sharpening flakes, which come off as people have struck the axe to make it sharp again once it becomes blunt, but you don’t find complete axes. The number of them that have come from the Thames suggests that people were making offerings of these objects. That continues of course throughout time. There’s been some excavation of prehistory in Southwark and certainly from the Bronze Age onwards this area was obviously very important. In fact, just on the other side of London bridge opposite Southwark Cathedral we think we’ve found a round barrow right on the edge of the river. So, I have no historical proof but I do wonder if this place held sacred memories; the reason perhaps that the priory of St Mary Overie was founded here in the early medieval period.

One of the things that keeps me coming back is that people simply want to know about the river and I’ve learned so much about it. I don’t really like writing very much but I do like sharing my knowledge – there’s no point in having it unless you share it, and a lot of the knowledge I’ve gathered over the years I’ve done so from people who were just so free with their own. Ali Taylor is one of them, Gustave Milne another. These people filled my head with ideas and knowledge and they made me want to learn more. A lot more recently I’ve been working with artists and seeing the wonderful results of them being inspired by the Thames, producing artworks that relate to the river and the fact that I played a little part in those projects has been wonderful.

I’ve noticed that when you take people down to the river they will, nine times out of ten, have something to tell you about a connection they have, such as an ancestor who worked in the docks or the shipyards over in Bermondsey. Each person has a different way of looking at the river, and all of these conversations add to my knowledge and help me to understand my own feelings about it .

What’s your most treasured moment, or memory of the river. And the worst?

The most amazing moment on the river was when I looked down and saw a piece of brick. Now there’s a lot of brick on the foreshore but there was something about this brick that made me bend down and pick it up. As I turned it over in my hand, I saw a dog’s paw print in it. I could tell by the clay that was used, the way it was fired and the thickness of the clay, that it was a Roman tile. The clay was only soft enough for a few hours as it dried to take that dog’s paw print and it has just the tip of the claws preserved in it which suggests to me that the dog was startled. The tiles were probably laid out in a field to dry, which might actually mean that the guy who made them was taking a pause and had sat down to rest. The dog would have arrived on the site and the guy might have shouted ‘Oi, get off my tiles’ (in Latin of course) at which point the dog paused for a split second with his paw just on the tile, before running off . That’s a small lump of stuff that most people would walk over, but for me it captured that second, and an interaction between the potter and the dog. When I have a show and tell of objects it’s one of my most popular; I have many fancier things, objects that are much more ‘valuable’, but that’s the one that most people are blown away by. It’s just someone’s pet dog being naughty two thousand years ago.

On the other hand, my worst time on the river was when I was meeting someone way downstream by Thamesmead. We walked down the stairs and as we got to the bottom to turn right there was a body lying on the beach. The body was swollen, it had obviously been there for some time. That was awful and very hard to deal with. We had to wait at the top of the steps for the Police to arrive – we couldn’t wait near it on the beach. That’s a really stark reminder of how powerful the river tide is but also the dark stories it tells. Generally, I see the river and the beach as a happy place, I’m down there with people discovering things from the past. This incident brought things right up to date, whatever it was it happened yesterday or the day before, and the present really came to the fore. It took a while after that for me to get back down to the beach.

What’s the biggest change you’ve seen?

There are two things I’ve noticed. From a broader point of view, it’s how from what were once derelict warehouses we now see huge luxury flats. The river was a place for working people, now to a large extent it’s a place for the rich. One of the first changes from warehouse to apartment was at Chiswick, and the original plan was to have the front of the building facing away from the river with a garden and a courtyard out front. It was through the work of local people, particularly Ali Taylor and the Chiswick Pier Trust, who managed to convince the developers to turn the development around so that it faced onto the river. So, in the end rather than having the garden as a focus they had a community space where Thames Explorer were based and now the RNLI (Royal National Lifeboat Institution) and a pier for community mooring. Around about 2000 the Environment Agency. had a major push to try and get London to face the river. They managed to persuade developers who soon realised that if people have a wonderful river view, their properties tend to be worth more. But it also meant that from being initially a busy working place, to then becoming a derelict space where only poor people would think about living, suddenly the London’s River became ‘the’ place to live, and that’s the way it stayed. At one point the warehouses blocked the river from the living areas, people could live one hundred yards away from the river and not be able to get to it. Sadly, these new developments have pretty much done the same thing. There are still working-class communities whose ancestors worked on the river who now have no view of it. It was a real problem in the 1990’s and largely thanks to the Environment Agency and other organisations, the Thames Path came into being meaning developers have to provide a walkway in front of their developments. So, in the end I think it’s actually helped bring the river back to Londoners. It’s become a lively, fashionable place, there are more opportunities and businesses; lots of cafes and bars.

The other thing I’ve remembered since I was young and coming with my Dad to the river, is how quiet it was. The docks had been closed by then, the city wharves had all closed and there was a lot of dereliction, but now the river is being used more again, we have river taxis going up and down which is great because people are noticing the river and appreciating it again. But the busy traffic along with rising sea levels, (which means rising river levels) and the increased rainfall recently, means that the river is eroding much faster than it used to. So, in some places where I went thirty years ago about a metre of the beach has been washed away and all the archaeology with it. So where as in the past you’d get scattered archaeology and objects everywhere, now there are whole areas where everything has been washed away and you find very little but there are still areas where the river is currently digging away at the beaches and there’s still plenty to find if you know where to look.

In the early 1980s when I first went down, there was no one on the beach, people didn’t really consider the river or beaches then, whereas now there are mudlarkers everywhere, tourists go down the steps at Bankside and over by St. Pauls so it’s become a much busier place. I don’t find that an issue, I tend to ignore people if I’m down there for my own spiritual needs, and I think there’s room for everyone really.

What would you like to pass on to future generations?

I think the most important thing I’d like to pass on is the fact that the river is a wonderful raw piece of nature running through the middle of London. There is still a lot that people don’t understand about the river, such as its tidal nature. Because of this we have freshwater and saltwater which means that environmentally it’s a vitally important place. Similarly, the City and the suburbs each have their stories to tell and the joy of it is that all of these stories can be told using the artefacts that you find on their beaches. I hope that people will come to appreciate that. I’d love to see for the river become prized and well-used as an educational resource. I’d like to see enhanced access, particularly for families with children. There are places where tourists can just wander down and be quite safe – the beach itself is safe, the access stairs are in good condition, but there are lots of other really interesting and special places where there is no access. I understand that there are issues of safety but there are certainly ways that the foreshore could be made more user friendly and safe. .

I’d like to see the river recognised as one of London’s largest, wildest open spaces. People often say ‘We have tamed the Thames”. No!, we haven’t! we’ve tried to tame the Thames but there’s no stopping it. One example is how throughout the 18th and 19th centuries people flattened the beach to be able to work on it. If you wanted to unload flat-bottomed barges they needed to lie horizontally, so you would straighten and level the beaches. Since the river went out of use as a trading and industrial centre those beaches have not been maintained in that fashion, so the river is digging away at the bottom and dumping at the top, all the while returning itself to its natural angle of repose (about 45 degrees). I like the idea that you have the manufactured barge beds and the natural angle of repose – the river will always make itself comfortable. You can see that going on now – the river is really taking hold, there are places where the water is undermining our flood defenses, thankfully the Environment Agency and the Port of London Authority are paying attention to that.

Who else should I speak to about this project?

Well, you already interviewed Duncan Hooson whom I would have definitely suggested. Another person I would interview is Raewyn Harrison who is a ceramic artist that I’ve been working closely with. We first came together through maps; she uses historic maps on her ceramics; I use them to learn about the past. Our minds meet in the maps. Once I introduced her to the foreshore, she started to use found objects in her work; sometimes whole artifacts, sometimes the subtlest of impressions. What I love most about her work is that through using maps and artefacts she gives them new life. She’s a contemporary ceramicist and there’s nothing historical about the style of her work but she makes wonderful references to the past. I think it’s great work and shows that the past doesn’t have to exist only in museums and books but can be used to inspire, and take on new meanings in today’s world. I hate the thought of artefacts going into dusty cupboards in museums or being stored in boxes under beds but by becoming part of a piece of contemporary artwork they take on new life and tell new stories. I think that is very important and exciting!

Another person you could meet is Ali Taylor who founded Thames Explorer Trust, she played a key role in bringing education to the Thames. When she opened Thames Explorer it was the first time that anyone used the Thames foreshore as an educational resource. Wonderful!

The other person you may be interested in speaking to is Jane Sidell who is Inspector of Ancient Monuments at Historic England, London. Her speciality is the Paleo-landscape, particularly the ancient Thames, so she knows all about Diatoms and rising sea levels and she was one of the first people in London to really push archaeologists into taking the Thames seriously and understand it from an environmental point of view.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Well as I’ve already mentioned I’m learning new things all the time. I come from a very working-class background and something I’ve become very interested in is work on the river and river-working people. I met Duncan (Hooson) and Julia Rowntree of Clayground Collective and they asked me if I’d do a foreshore walk with ceramicists and I thought this would be fun! I mainly talked about how important ceramics are to archaeologists, particularly with dating. What was interesting was these people were picking up objects and listening to me saying well we can date this to whatever by looking at whatever, and they would say isn’t it wonderful the way this handle has been pulled. I’m thinking ‘pulled?’. What do they mean? They were talking about manufacturing, and I never thought about it before. I was quite aware of fingerprints. I love fingerprints. If you put your fingers in those prints on that pot you are putting them in exactly the same place that the potter put theirs, hundreds or even thousands of years ago. But the ceramicists were saying, ‘yes but look on the inside, you can see where the fingers were used to attach the handle’. Now one of the main things I take home with me from the beach is evidence of the maker. For example, the marks that a butcher makes while cutting bones can tell us what cuts of meat he or she was producing. Round-bottomed medieval pots were made that way because they sit best on uneven surfaces but if you put them onto a flat solid surface, they will of course roll. So, one way of dealing with that was to put pinch marks around the bottom, to stop it rolling. An eight-year-old child came up to me on the beach saying ‘Look, my fingers fit’, and indeed they did! Even allowing for shrinkage in firing , this proved that medieval children were employed, not as slave labour in a factory but in the family business, learning the tricks and tools of the trade. That is just one way that, on the Thames beaches, you can make direct contact with our shared past.

Mike Webber is a community archaeologist, educator, and curator. He coordinated the Thames Archaeological Survey 1995-2000 and now specialises in the archaeology of the River Thames. The focus for this work has been the artefacts, particularly pot sherds, found on the Thames beaches. Recent work with ceramic artists and makers has led Mike to explore the archaeological and historical evidence for the people who made these artefacts and the techniques that they used to manufacture and decorate them.

Mike Webber is a community archaeologist, educator, and curator. He coordinated the Thames Archaeological Survey 1995-2000 and now specialises in the archaeology of the River Thames. The focus for this work has been the artefacts, particularly pot sherds, found on the Thames beaches. Recent work with ceramic artists and makers has led Mike to explore the archaeological and historical evidence for the people who made these artefacts and the techniques that they used to manufacture and decorate them.

Thames Archeological Survey. http://www.thamesdiscovery.org/riverpedia/the-thames-archaeological-survey

Ali Taylor. https://soundcloud.com/thamesfestivaltrust/life-afloat-ali-taylor

Thames Explorer Trust. https://thames-explorer.org.uk/

Gustav Milne. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustav_Milne

Chiswick Pier Trust. https://chiswickpier.org.uk/

RNLI (Royal National Lifeboat Institution) https://rnli.org/

Environment Agency. https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/environment-agency

The Thames Path. https://www.nationaltrail.co.uk/en_GB/trails/thames-path/

Port of London Authority. http://www.pla.co.uk/

Raewyn Harrison. https://raewynharrison.com/

Jane Sidell. https://www.linkedin.com/in/jane-sidell-42214446/?originalSubdomain=uk

Duncan Hooson. http://www.duncanhooson.com/

Julia Rowntree. http://www.jrowntree.co.uk/

Clayground Collective. http://www.claygroundcollective.org/