THE WEST ELEVEN HOUSING COOP INTRODUCTION

There were three factors at work in setting the need for a housing co-op in London W11 by the 1970s. Firstly, there was the national crisis of the physical deterioration of the largely 19th-century housing stock in Britain’s inner cities after three depressions and two world wars, and the concomitant rise in homelessness and unmet housing need in the post World War II period. Secondly, there was a particular concentration of those factors in the Notting Hill, Ladbroke Grove and North Kensington district, owing to the peculiar history of the local housing stock. Those first two factors created a need for decent housing of any sort. Thirdly, partly arising from that history, there was a large group of educated “bohemian” baby-boomers living in W11 by the 1970s, largely inadequately housed, who had been attracted to the area by various social and cultural factors; they found themselves with particular needs, and had the potential motivation to create housing co-ops to try to meet those needs.

In the middle of the 19th Century – 1840s to 1850s – there were in the rural district that is now London W11 two main land users: the Portobello Farm, and the Ladbroke Grove stud and racecourse. In, if I recall correctly, the 1860s, both of those closed, and property speculators bought the land to create housing for sale to Britain’s then rapidly growing middle class. The problem was that by the time these houses were built in the 1870s, the British economy had hit a recession, so the five-storey houses, intended for a family and servants, did not sell.

Among the first properties his by this crisis were the unusual “back-to-front” terraces of Powis Square and Colville Square, with the ugly functional sides facing the street, and the pretty sides with the large bay windows facing the private communal garden parks. These and many other large houses built for sale were thus from the start of their useful lives multi-occupied, let off to tenants a room or a floor at a time; and in this condition they continued to be used right up to the 1970s. Over that century or so, most of the changing landlords did not make enough money from rents to keep up with the frequent and cumulative repairs the houses needed, even if they had been inclined to do so: which being, for the most part, rapacious, penny-pinching petty capitalist exploiters, they were not.

There was another depression in the 1890s, followed soon after by the disruptive effects of the Great War of 1914-1918. During major wars, shortages, of money, men and materials meant no maintenance or repair work got done on most the housing in Britain’s inner cities. Then in the 1920s there was another depression and years of economic chaos across Europe, followed soon after by the Wall Street Crash of October 1929 and the Great Depression which lasted until World War 2 (or, in Germany’s case, the build-up to it) revived the depressed economies. Not that such mobilisation made life prosperous for the small-scale landlords of Britain: quite the reverse in fact, given the activity of the Hermann Goering Aerial Demolition Gesellschaft from June 1940 to February 1944.

Now while it is true that from about 1870 to 1970 housing stock in all the UK’s major cities suffered from the same stresses, in Notting Hill and Ladbroke Grove the stress was worse than in most other districts. The almost complete lack of a significant owner-occupier class, with its culture of investment, responsibility and self-reliance, meant that most of those tall houses continued to be either maintained in a desultory fashion at best, and more often dangerously neglected, and continued to be multi-occupied.

Now while it is true that from about 1870 to 1970 housing stock in all the UK’s major cities suffered from the same stresses, in Notting Hill and Ladbroke Grove the stress was worse than in most other districts. The almost complete lack of a significant owner-occupier class, with its culture of investment, responsibility and self-reliance, meant that most of those tall houses continued to be either maintained in a desultory fashion at best, and more often dangerously neglected, and continued to be multi-occupied.

After the end of World War 2 in 1945, the housing pressure in the area increased. Substantial groups of people displaced by the war and its consequent political changes in Europe sought refuge in London, and many gravitated toward W11 for the cheap (if rough) housing, as well as to congregate with other members of their ethnicity. Irish people had long migrated to London, since the potato famine of the 1840s, and were strongly represented in W11. They were joined, after 1945, by Poles, Jugoslavs, Magyars, Czechs and others; then the continuing migration of Afro-Caribbean and other British Commonwealth peoples in search of improved economic opportunities also got under way at that time, and this added to the already complex mix and to the pressure on housing availability, along with (later on) Cypriots and Moroccans; also Spanish, Portuguese and Latino-American refugees from repressive or fascist regimes, and others.

The result was that much or most of the rented housing between Westbourne Grove and the canal became even more intensely multi-occupied, overcrowded and run-down. In the 1950s, the Hungarian gangster Perel Rachman became a byword for the viciously and thuggishly exploitative landlord in W11, “rack-renting” properties, subdividing rooms to increase the rentals. I later lived in two of his properties, by then owned and managed by one of his minders.

By the mid-1960s a catalyst for action was added to the mix: partly educated or over-educated baby-boomer “bohemian” types, younger people escaping abusive or repressive families and looking for the freedom to live their own lifestyles, often involving intellectual, political and sexual freedom (gay and hetero) which they could not find in their stuffy families of origin in the repressive suburbs or regional areas, as well as booze, drugs and rock music, late-night fun and so on. The search for alternative lifestyles and creative self-expression involved, for some, overt political activity. Those boomers included me: I moved into a shared flat in a run-down house in Powis Square in 1966 as a student.

Most of those boomers, however, lived in insecure overcrowded housing, subject to frequent changes, serial episodes of urgent moving and occasional homelessness. Thus it was for me. So, by the 1970s Notting Hill consisted of a complex mix of more or less deprived and disadvantaged groups: people of foreign origin and Commonwealth immigrants, all with less than optimal earning power and often facing racial discrimination in housing; single parents, disabled people and the (at best) semi-employable lumpen elements of the boomer influx, as well as a continuing throughput of students, shift workers, part-time employed people who spent half their lives on the dole or on sickness benefit, petty criminals, artists, dissident intellectuals with MI5 or Special Branch on their tails, musicians, writers and the like, who lived on erratic and often inadequate incomes. As well as lacking purchasing power to get them into better housing outside the W11 ghetto, many of these people (especially the singles or childless couples) lacked the qualifications for the tiny and grossly inadequate supply of public or subsidised housing in the area.

That describes the background of unmet housing need in Notting Hill, North Kensington and Ladbroke Grove. In my other main essay below, in which I sketch out my role in the foundation of W11 Co-op, I will also describe how some of these bohemian types provided the main clientele and the willing workers, as well as the background grassroots political action process by which the ground was prepared for the seeds of housing co-ops as a contribution to solving the problem of unmet housing need. There was resistance, organization and agitation, people demanding improvements in their (our) lives.

As I outlined in Part 1, there were two main elements in the historical background to the development of W11 Housing Co-op:

1. the decline of the national housing stock in Britain’s inner cities, since most of it was built in the 19th century; and

2. the particular history of the speculatively-built housing in Notting Hill.

These resulted in much unmet housing need by the 1970s, especially among the boomer bohemian influx.

For co-operatives to be potential contributors to the solution however, another and quite distinct element was needed: ideology, accompanied by motivation, determination and commitment. The necessary precondition for top-down organizational housing provision is simply that of unmet housing need. The necessary preconditions for housing co-op action are that the affected punters:

a) have no faith that conventional housing providers are going to do anything for them, and

b) believe that they must therefore band together, work and organize to bring about change.

It is the same as the difference for workers between trusting the bosses to look after them (as if the bastards would!) and joining a union.

In the early 1970s, the vast majority of the local working class and doletariat in North Kensington wanted someone else to provide them with housing: private landlords, the local authority or other purpose-oriented agencies. While there is a valid argument that the paying of taxes and rates entitles the payer to the provision of services by the relevant layers of government, there is an equally valid argument that in adopting that attitude, the punter hands over his power along with his money, and surrenders the right to wield any influence over the conditions of his or her life. The boomer bohemians, many of them, came to the Notting Hill situation with already developed political perspectives, and were ideologically much less inclined to do as the local proles did. The boomers were possessed of highly critical perspectives on authority in general and the capitalist political economy in particular, and this educational-cultural factor meshed with the tight eligibility rules of the local authority and the charitable housing associations to create a pool of inadequately housed and disentitled people who were pissed off enough by their exclusion to do something about it. Co-ops in many ways potentially fitted the bill, including by their resemblance to the communal experience of flat-sharing, house-sharing and squatting which many boomers had experienced as largely positive. And that response occurred not in an ideological vacuum but against the background of increasing political action in the area.

By the 1970s, there had for some years been a growing political movement demanding and working for change in the conditions of people’s lives, operating on a variety of fronts. The history of that movement, which was a very important background factor behind the co-op thrust, begins with a look at the traditional Marxist critique of capitalist society as espoused by the Communist Party and others at the time. In that view, all power in society is based in the political economy, in class relations in the sphere of production. By the 1960s, a dissident or heretical view was gaining ground: the idea that the other half of the economy, the sphere of consumption, was just as important as a locus of power and determinant of social and political outcomes. For most of the time since Marx and Engels began to write their seminal works in the 1850s, the sphere of production had been seen (somewhat distortedly, in fact) as an exclusively male preserve. There was, therefore, a great deal of implicit sexism in the traditional Marxist view – the idea that power in the political economy essentially grew out of the biceps of blokes, amplified by the hard blokey products (and tools) of coal, iron and steel. This view of course ignored the vital direct contributions of organized women to the working-class struggle in the 19th century, such as the match-girls’ strike of the 1890s, and the entry of millions of women into previously blokey jobs in times of war, in 1915-1918 and 1940-1945. It also ignored the massive contribution to the economy of female homemakers, wielding market power by spending their and their blokes’ earnings.

By the 1970s, the writings of dissident Marxists and other progressives such as Antonio Gramsci, Danilo Dolci and various anarchists, as well as the critiques of the third-wave feminists, were circulating widely among the post-WW2 newly educated sons and daughters of the old working class, the first beneficiaries of essentially free university education. Those new critiques formed part of the burgeoning ferment of intellectual ideas in wide circulation since the cultural revolution of the mid-1960s exploded in political demos, rock concerts and other events in the parks and streets of Berlin, Paris, London, Chicago and elsewhere. The young left’s revolt against the obscenity of the mass-murderous US war in Vietnam was fought out in the cities of Europe and the USA.

The new ideas also circulated among members of the older organised left, many of whom were willing to reorganise in response to changing objective conditions and new ways of regarding the political economy. One of those new organisational forms since the late 1950s had been the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), representing a broad alliance of rebellious and unconventional lefties, Christians, anarchists and others. It organised the annual Easter march from the government nuclear warfare research establishment at Aldermaston, out to the west of London, to Trafalgar Square. Out of the many meetings of minds that CND facilitated there grew a new multi-purpose front, the Committee of 100, which (if I recall correctly) was explicitly dedicated to developing new ways to manifest dissident and radical political critiques. Some of the members thereof, such as John and Jan O’Malley, worked afterward to stir up the hitherto powerless classes of W11, forming the Notting Hill People’s Association (NHPA), an essentially open and informal broad-left front to promote struggle on local issues. It was the time of ‘issue politics’, or “think global, act local”, of a million blows against the global capitalist empire, small blows delivered by previously powerless people finding their voices, organizing to take control of their lives, struggling to improve conditions. The comrades (including some of the more open-minded CP and Labour Party types) set about organizing the kinds of people whom the old male left had dogmatically regarded as unorganisable: women, immigrants and lumpen elements.

One of the first struggles, in the late 1960s or early 1970s, was over the closed garden squares, Colville Square and Powis Square. These were fenced-off and locked private gardens for the exclusive use of residents in the adjoining blocks. Local parents had long been pissed off because of the lack of safe playspace for children in that part of W11; there were at the time no pedestrian precincts, so kids just had to play on the footpath, and risk injury every day. The NHPA therefore organised a series of demonstrations in which people with placards broke into the gardens and occupied them for a while, with as much publicity as possible. Eventually, even the Tory grandees in Kensington Town Hall saw the sense of the NHPA’s demands, bought the squares and opened them up for everyone. Another struggle, closely related to that one, was the campaign for subsidised daytime childcare facilities, which eventually succeeded.

Another community organisation which partly grew out of the same campaign group was the North Kensington Law Centre (NKLC), a solicitors’ office set up to support the disadvantaged of the area with free advice and court representation. It specialised in crime, housing and employment litigation. Crime was an issue especially for the local youth, whom the police picked on relentlessly, and often framed or verballed; housing was a constant struggle for repairs, for rent reductions, and against harassment and illegal evictions. Employment cases involved workplace harassment, bullying, sex discrimination and unfair dismissal, as well as underpaid wages. NKLC, the first free law centre in the UK (the first in the world had recently opened in Boston, Massachusetts) was generated by a long backroom campaign led by founding lawyer Peter Kandler, opened its doors in 1970, and is still going strong.

And then there was the biggest bugbear, housing. Many NHPA members had been campaigning in various ways for years on this issue, and there was little progress by the early 1970s. Eventually, in response to the continual noise, the Council decided to conduct a survey of housing conditions. This did not fool the NHPA folks. They knew that there had been plenty of surveys done before, that well enough information existed for the council to act, and that another damn survey was just a way for the council to avoid taking any real action to change the realities on the ground. They convened a public meeting on 2nd August 1972 to launch the survey, in a council hut in Tavistock Road; The People responded by locking the bastards in for a while. The huge publicity was garnered a few months later, on 8th May 1973, after a street publicity campaign lasting several weeks on the pedestrian precinct in front of All Saints’ Church. I manned the information desk for most of that time, often accompanied by a spook – I never found out whether he was from the Metropolitan Police Special Branch or MI5 – who had tried to bolster his credibility with a planted story in the local paper about the “Battle of the Charities”, which was a put-up job by him and his old military chum James Fraser Horne, who ran one of the charities helping the street homeless. The spook thought we were taken in, the bloody idiot. He must have held lefties in a lot of contempt.

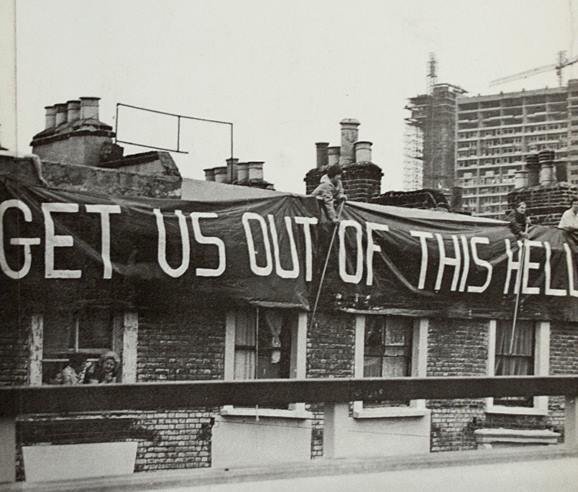

The Council held their second public meeting, to present the survey results, and this time we locked them up all night – with entertainment provided by musicians, poets, and fornicators under the panel table. In the morning, Council fuhrer Malby Crofton raged “I’m not doing any deals with bloody anarchists!” The senior copper on the spot, however, was not to be thus commanded, and sensibly agreed to make no arrests if The People let the Councillors and their wives and satraps go, and we all walked out peacefully – which is what happened. For a week or so, the publicity was magnificent, and the “Siege of Notting Hill” brought The People’s complaints about atrocious housing conditions to national attention. And our spook reported to his political masters that while there probably wasn’t much danger of the Notting Hill People’s Association replicating the Russian Revolution, it would probably be a good idea for the two levels of government, especially the national one, to do something about the problem. About a year after the Siege, Whitehall found five million quid which they had previously said they didn’t have, to subsidise a huge buying campaign by the local housing trusts, Notting Hill Housing Trust and Kensington Housing Trust. And that was a vital development. for without that injection of cash, and continuing support from central and local government, the housing co-ops could not have succeeded in putting roofs over our members’ heads.

I grew up in housing insecurity. My alcoholic father, traumatised in World War II and a hereditary Aspergian, did not build up any savings, and neither did my brain-damaged and equally traumatised mother – so, that dysfunctional family never got onto the ladder of home ownership. My parents’ relationship was as unstable a my father’s employment, so by the time I was ten I had lived at six addresses, including those of my nan and my father’s parents. When my mother pushed me out of the seventh address at the age of 15, my socioemotional and employment difficulties were already apparent, so I had no chance of consistently earning enough to even contemplate home ownership on my own. I was left dependent, like many others, on cheap and insecure rented accommodation. That all added up to a powerful motivation to seek a proper housing solution.

In fact, the concept of organised co-operation was a routine aspect of my childhood. My mother and her close relatives were members of what was referred to as “the co-op”, a network consisting of regional retail co-op department store chains such as the London Co-operative Society, all of which were in turn members of the Co-operative Wholesale Society. The profits of the enterprise were distributed annually to members in proportion to their purchases over the year. The trouble was, by the start of the 1970s, trade and membership were declining, and the organisation was moribund. The range of goods was terminally old-fashioned, dictated by the staid, conservative and outdated taste of the ageing directors. The fashion and design revolution of the 1960s had passed them by, they remained stuck in the 1940s and 1950s, and they had lost a whole generation of potential members.

I arrived in Notting Hill in October 1966, having already experienced over three years of inadequate or insecure housing since I was forced out of the abusive family home. I and two fellow students rented a flat in one of Rachman’s run-down houses; that was the start of another period of poor housing and frequent moves, punctuated by homelessness.

My first contact with what was in effect a housing co-op was initiated in the summer of 1968, when I did some voluntary work with the Notting Hill Children’s Project (NHCP), an informal weekend and holiday thing run by a group of professional friends who shared a house in North Kensington. They gave country outings in their own cars to the most deprived kids they could find, often on the recommendation of Social Services. Many of those kids had never been outside the ghetto, had never seen the countryside, and didn’t even know what a cow was. The group needed extra hands to help and play with the kids, and I was one of those. A year or three later, their landlord gave them all notice to quit in order to sell the house, and in response they came up with a solution: they registered a housing association to buy the house, and rented it back to themselves. Constitutionally, it wasn’t the ideal fit, but it served the purpose; and that HA was one of the factors which led to the development with the Registrar of Friendly Societies of specific rules designed for housing co-ops.

In the early 1970s, the problems my partner Annie and I had in getting and keeping decent housing led to us opening what became a spreading squat, in Latimer Road W10. Those small, ageing and dilapidated houses had been bought up by the local authority and were gradually being emptied, waiting for demolition and the complete redevelopment of the area. That sort of thing was going on throughout London and other cities at the time: rough but still livable houses were being kept empty which thousands of people were homeless, or close to homeless. Thus arose the squatting movement. People entered (preferably with minimum damage which they quickly repaired) and took up occupation. Squatting was never a crime, though some police and other thugs did need to be reminded of that. The movement became quite widespread, and gave rise to the later phenomenon of short-life housing, also inaccurately known as licensed squatting, in which building owners, usually institutional, issued short-life occupation licences to needy homeless people. That squatting experience, and the work of the NHCP chums, led Annie and me to launch Abeona Housing Association (named by Annie after the Roman goddess of home and hearth). We used it to apply to the Greater London Council for short-life housing, but the application got lost in the massive bureaucracy of County Hall.

In 1973 I was heavily involved in the publicity campaign which led up to the “Siege of Notting Hill” (see Part 2 above); and a little while after that, the elements of the launching of West 11 Co-op started to coalesce. I had also been volunteering at NKLC while on sickness and disability benefits, and that experience turned out to be very helpful in many ways. Firstly, at NKLC I met the late Anna Malcolm, who became a good friend and was very important in the founding of W11 Co-op. She knew a lot of people who were in housing need and not eligible for the usual institutional solutions, people whom she thought would be strongly interested in the co-op possibility – as indeed they mostly turned out to be. She introduced several of them to me or sent them to the exploratory meetings once those got under way. And of course word spread then to other people in the same position.

It was in 1974, if I recall correctly, that a specific set of model rules appeared for housing co-ops. I vaguely recall that the recently formed co-ops service agency (or “secondary co-op”) Solon (named after the mythical ancient Greek lawgiver) was involved in developing and promoting them. Housing co-ops were in fact nothing new in the world: in a variety of shapes, they had been making contributions to the solution in many countries for decades, but they just hadn’t taken off in the UK so much.

Thus interested parties and prospective members began to meet, and to discuss the formation of a housing Co-op. Many of those people, being good alternative lefties, basically didn’t trust governments, laws or institutions, so rather than just accepting what others had done, they wanted to discuss the model rules clause by clause, and change some to suit our purposes. This is where some of my previous experience came in useful: from my previous encounters with adapted housing associations and knowledge of the work of the Registry of Friendly Societies, I knew a fair bit about the relevant laws and the reasons behind them, and my work at NKLC had expanded my knowledge of the legal jargon and terminology. Thus I was able to lead the exposition of the language of the model rules and explain most of the purposes of the clauses, to the apparent satisfaction of most of the skeptics. That was not all that took up two years of almost weekly discussions; there were also the need for and the role of service agencies to supply the housing we would use (the role eventually filled by Notting Hill Housing Trust), the division of responsibilities, the tasks that would be left to the co-op members such as rent collection and reporting, low-level maintenance (except where we had qualified members), tenant selection, accounting and other matters.

For much of those two years I chaired those meetings and led the discussions. Some people chafed a bit under what they saw as my somewhat domineering style, and told me so. I did my best to keep the discussions in order and on topic, keep people’s attention focused, prevent straying off the subject and time wasting, and bring meetings to clear decisions on how we would proceed. Since many of the members had no experience of participating in formal and purpose-oriented meetings (and sometimes showed it), the necessary discipline had to be imposed, or we would never have got through all the discussions and made the important decisions, so I gladly take full responsibility for being a bit of a pushy bugger. In that way, my Asperger’s syndrome was a bit of a mixed blessing: it enabled me to ride fairly roughshod (though not always too rudely, I hope) over indiscipline, and it also ruffled some feathers, naturally. I possibly could have done it all with rather smoother diplomacy if I had been a normaloid; but I wasn’t, so things happened as they did.

At some point in 1976 we completed the agenda, having amended the wording of some clauses where that wording was not fixed by the requirements of the relevant Acts; members signed up, and the co-op was formally registered. We ran a couple of fundraising entertainment gigs in All Saints’ Church Hall to raise the fees. Then we signed up to the Service Agreement with Notting Hill Housing Trust (preceded by another long and detailed discussion, of course) and started the committee work of selecting the first batch of tenants, appointing volunteers for various tasks, and developing our administrative routines – some of which were required by NHHT, which made life a lot easier than nutting them out from first principles.

I think the gestation period (I remember it as being almost two years) turned out to be a good thing for the co-op’s cohesion and durability. Those two years of weekly meetings and intellectual struggle meant that the launching members, by the time we signed the forms, were on the same page in regard to the nature, procedures and structure of the co-op, were clear and united in our purpose, and all had the same things invested in the co-op: time, effort, brain-ache and a bit of grief – and we were not about to walk away from that investment, whatever challenges the future brought. We had been through all the ideological stuff, and were now together for a clearly understood practical purpose, that of getting roofs over our heads.

I did not become one of the first tenants, as there were other people in more acute and urgent housing need than I was by then. I had been housed in, initially, short-life housing by NHHT since about 1975, as an essential community worker. I still needed a Co-op flat later on though, as Annie and I, joint tenants of the permanent NHHT flat which followed the short-life, broke up and she claimed a tenancy in her own right (as well she might). So in 1980 I moved into my W11 Co-op flat with my then 13-year-old son.

As it turned out, I only stayed there about 18 months, as by then I was getting a bit stir-crazy after 15 years in the ghetto, was looking for fresh challenges, contracted a nasty attack of Hinduistic meditation religion, and moved away. But that is another story. On the way to that departure, I also advised the prospective members of Portobello Housing Co-op and others, worked for a short-life housing co-op in north London for a year or so, and founded a short-life housing co-op for the religious group, which succeeded in obtaining several large homes for use as ashrams through the 1980.

The housing co-op movement in Britain foundered in 1979, just as it was set for a dramatic take-off. The Labour government of James Callaghan, reeling from the cumulative financial effects of the OPEC oil price hikes after the 1973 Yom Kippur War, invented swingeing public spending cuts: and as always, the special project funding – for example, that for housing co-ops – was the first to be axed. So, a lot of hopes bit the dust that year. I’m very glad W11 C o-op got launched before all that came about.

I was not the only hard worker involved in the two-year launch process of W11 Co-op. Without the active, eager and determined participation of the forty-odd people who ended up signing the final rules and the registration papers, all my effort would have meant nothing, so I hereby pay tribute to the stickability and determination of all the early participants. Congratulations to all concerned on the long survival and self-evident success of West Eleven! We did it for us, together, and after 35 years it is still going strong.

When Linda Saunders and Steve Mepsted contacted me on the other side of the planet to invite my participation in this exercise, I was delighted to find out that W11 Co-op still existed and prospered. Indeed, the effort I put in to helping launch it, and the salutary results, form the achievement of which I am most proud. This is a rough memoir, hastily put together some 37 years or more after most of the main events. It presents the story as far as I can remember it.

If anyone thinks they remember any of it more accurately, please let me know, at: jasoncopeland@y7mail.com

© Jason Copeland, 28th September 2011, 29th October 2011