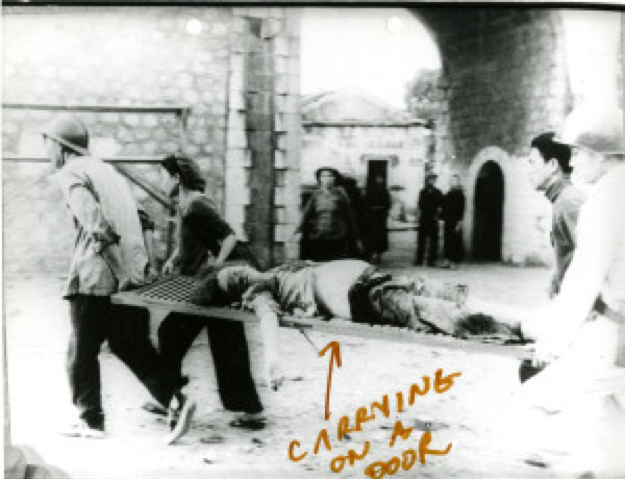

Vietnam – archive photograph annotated by Stanley Kubrick while researching and making the film ‘Full Metal Jacket’

The Vietnam War

has become embedded in the cultural imagination, memorialisation and self-image of Americans (and indeed South-East Asians). This paper serves to unpack some of the issues surrounding the mediation of the conflict through the Vietnam War Cinema of Hollywood. This genre of The Vietnam War Movie is essentially the genre of (the response of Hollywood to the American defeat in Vietnam) It forms only a small part of the chronology of War Cinema and it is particular in that it deals with issues of self-identity and the need to reaffirm a position; to address and alleviate a trauma; thereby restoring credibility and self-belief to an American public. I am also choosing to review these issues via analyses of the Graphic Imagery found on the poster for ‘Full Metal Jacket’. I have chosen this particular film for two reasons; firstly because in film terms I think it holds an unusual place in the cycle of Vietnam War movies, this is for a number of reasons, which shall be discussed. Secondly because it is a Stanley Kubrick film, and is therefore a practical work to discuss for this particular paper, which is submitted in response to research within the context of ‘The Stanley Kubrick Archive’

Early in the chronology of War Cinema, films were made to lend shape and structure to a cultural imagination. This is an arrangement, an implicit understanding that goes as far back as 1918 when D.W. Griffiths World War I propaganda film ‘Hearts of the World’, was given financial backing by the British High Command. Guy Westwell in his book ‘War Cinema’ – ‘Hollywood on the Frontline’ summarises this propagandist role between moviemakers and military policy-makers.

‘…the armed forces have considerable power in shaping scripts and will often withdraw support if a film is perceived to be unflattering…in courting the favour of the military, an institution with a significant vested interest in war, Hollywood tends to produce movies that are, to put it crudely, pro war…(they) show war as necessary…war is almost always shown in a positive light’ (Westwell. G. pg 3) (1)

Hollywood was initially slow to tackle Vietnam in shaping the cultural imagination of the War.

‘The US Military was unwilling to provide their cooperation and support for films that might criticize the war, making war films an expensive and risky commercial proposition’ (Westwell. G. pg. 60) (2)

Michael Herr in his Vietnam War Novel, ‘Dispatches’ noted, ‘Vietnam is awkward, everybody knows how awkward and if people don’t want to hear about it, you know they’re not going to pay any money to sit in the dark and have it brought up’ (Herr. M. ‘Dispatches’ 1978) (3)

Hollywood did address the war obliquely in a group of films that displayed a ‘Vietnam Subtext’.

‘This tendency is seen in Westerns such as ‘The Wild Bunch’ (1969) ‘Little Big Man’ (1970), and ‘Soldier Blue’ (1970) but also in movies that portrayed World War 1: ‘The Blue Max’ (1966) and ‘Darling Lili’ (1970). World War 2 is also treated cynically, with a parodying, inverting and satirising effect. This can be seen in a particular cycle of films including ‘The Dirty Dozen’ (1967), ‘The Devils Brigade’ (1968) and ‘Kelly’s Heroes’ (1970) ‘All these films can be read as an index of Vietnams’ divisive effect on American society.’ (Westwell. G. pg 61) (4)

But still Hollywood did not tackle Vietnam directly, partly because of a political necessity not to address the issues. It was only after the eventual return of the American troops in 1975 that Hollywood saw the opportunity to address the war head-on. In the late 1970’s the first offerings were released: ‘The Boys in Company C’ (1977) and ‘Go tell the Spartans’ (1978) closely followed, and with more critical acclaim, by ‘The Deer Hunter’ (1978) and ‘Apocalypse Now’ (1979) All of the above movies were independently financed and produced. The Military and the Pentagon, now buoyed by films that had hit a cultural nerve, (re) launched their willingness to provide military hardware, warships, airplanes, uniforms, and also real soldiers who acted as extras and advisors. A whole raft of films informing the cultural imagination and ideologies of Americans were made in the 1980’s which directly addressed the traumatic experience of the Vietnam War: ‘Platoon’ (1986) and the ‘Rambo’ Movies – ‘First Blood’ (1982) ‘Rambo: First Blood II’ (1985) and Rambo III’ (1988) are prime examples of a ‘Hard Bodies’ (Jeffords 1994, p 13.) approach to Vietnam fostered by the historical revisionism of the Reagan years. To digress for a moment – there is a telling incident of this phenomenon in ‘Full Metal Jacket’. R. Lee Ermey was a Vietnam Veteran with the Marine Wing Support Group 17 in 1968. He first played a Marine Drill Instructor in ‘The Boys in Company C’ (1977), which brought Ermey to the attention of Stanley Kubrick. He was drafted in to advise Kubrick for the early boot camp scenes and was so unnervingly good at it he became the character of Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, acting to great acclaim; satisfying both the audience, and Kubrick of an ‘authentic’ military experience. War Cinema has always, and is still, held in sway by this persuasive undercurrent of the support of military policy makers and the government, so much so that one can argue that any war film is a collaboration of mutual understanding, between writers, producers and the directors of films, the funders and investors who back the films, the production teams, who publicise through posters, trailers and secondary imagery, and the audiences and critics who see the finished product. The war movie is only truly understood as a set of indices to war itself.

‘It is only through this indexical relationship between the war movie and war proper, a relationship which is complex, indirect and contradictory, and yet also constitutive, that we can glimpse and begin to articulate the interconnectedness of war, movies about war, and the cultural imagination of war more generally’ (Westwell. G. pg 4) (5)

When Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990 George Bush famously said that there would be ‘No More Vietnams’ and opened up Hollywood to a difficulty: how to fully comprehend and represent American activity in smaller-scaled wars in ‘new’ localised, ethnic territories. Vietnam had continued to provide Hollywood producers with revisionist opportunities but now it had become an unsatisfactory icon for making sense of the war in ‘present’ terms. Having prefigured the movement of the Vietnam War Film through the 70’s and 80’s and proposed that by the late 80’s America found itself once again turned around full circle, with a lack of any response to the changed nature of war and facing difficulty in portraying war post-Vietnam. I now need to return to the late 1980’s and begin to consider the film ‘Full Metal Jacket’. Made in 1987 by Stanley Kubrick it was part of a small and short- lived cycle of films, which attempted to revise and question the typical conventions of the combat movie.

‘Without a coherent ideology to shore it up, the war film becomes directly incoherent, for example narrative trajectories that fragment into monadic bits in Full Metal Jacket, with its two major segments and it’s numerous set pieces’ (Eberwein. R. Pg 56) (6)

The film does indeed seem spilt in half. The opening section of the film is claustrophobically based in the boot camp where Gunnery Sgt. Hartman drills new recruits. The second segment of the film has often been quoted as a ‘series of set pieces’ fragmented in places and staged in appearance. The sniper scenes at the end of the movie lead to Joker’s realization of his own masculinity and capacity to kill. This is the ‘denouement’ of the film, and the meaning behind the ‘duality of war’ statement that Joker makes to a Colonel who challenges him on the two conflicting messages that appear on Jokers helmet: a peace symbol badge and the lettering ‘Born to Kill’. The ‘duality of war’ is also the duality of man. Joker at the end of the film, states that despite being “in a world of shit” he is glad to be alive, and is unafraid. In this way one can see the second part of the film as a continuation of the journey of Joker.

The following is from “La Figaro” – extract from taped interview by Francoise Maupin with Stanley Kubrick on Full Metal Jacket and found by the author in The Stanley Kubrick Archive at London College of Communication

Francoise Maupin: “Your hero was wearing on his cap ‘Born to Kill’ and a Peace Symbol (Badge) I thought the Colonel would make him put it away. Do you think it was possible for him to keep this thing all the war…?”

Stanley Kubrick: “I think it’s possible. I mean someone might have said, ‘throw it away’ but they wouldn’t necessarily make them throw it away – I think its possible”

FM: “I think it’s a very good symbol”

SK: “Oh Yea!”

FM: “And it’s speaking about the duality of many things, which is very important, and at the same time you speak about Jung. You say the ideas of Jung concern the duality of Man. Are you interested in Jung’s works?”

SK: “I’m certainly interested in the idea that’s he’s joking about, which is obviously one of the main ideas of the story. That is the inability of man to see the shadow-side of himself, to blind himself every-way possible from seeing that side of his nature”

I would like to make a shift in emphasis from the ‘Filmic’ to the ‘Graphic’ (and the ‘Photographic’) continuing the theme of symbols in analysing the film poster for ‘Full Metal Jacket’ and the use of photographs in ‘Platoon’. We have discussed the nature of the war film as an index of meanings, which set out to contextualise and make understandable, complex National and individual issues at a given time in history. If we accept that each film is a piece of politics in itself then surely the poster, the graphic representation of the film operates as of the main ‘ports’ or channels of advertising, locates itself as the vehicle for the attainment of a sort of ‘image-reservoir’: that triggers responses, reassures and reinforces imagination, while simultaneously reaffirming (the film’s) politics to the (intended) audience. I would argue that given these terms the war movie could be seen as an extended advertisement – an exercise in branding – not of a product necessarily but of an ideology or a set of ideologies. The movie poster is then the advertisement for the advertisement. It is a simple fact, demographically speaking; that we are far more likely to see the film poster for a movie than actually view the movie itself. The poster therefore, I believe, is a powerful tool of advertising, even if its ultimate goal (to get people to see the movie) is not realised. The Graphics, designed and displayed upon the poster surface; appearing in hundreds of locations in a huge variety of formats ‘emblazon’ our understanding of the content of the film through sophisticated use of iconographic images: explosions, bullets, helmets, action, comradeship, blood, sweat and tears. The job of the poster is done: helping to ‘mythologise’ the War, in cultural memory and imagination. The ‘Graphic’ of course, borrows heavily from the ‘Photographic’ and there are good reasons for this: the makers of war films, and Stanley Kubrick was no exception, would often use imagery from photo-journalism; historical artefacts from the real events. Events that the film hopes to depict. An example is the use of photographs taken by Ron Haeberle (7) of the killing of civilians by American soldiers in My Lai. These photographs were published in Time Magazine in 1969 and are well known. They helped contribute to the mediated experience of the war. The use of these photographs in films is interesting. Kubrick looked closely at many photographs by Philip Jones Griffiths, Don McCullin and others and also engaged in this re-enactment process mainly to define detail of clothing and facets of architecture, but also in one scene where a wounded soldier is carried to safety not on a stretcher, but on a found door – a direct re enactment of a photograph seen above bearing his own annotation.

‘As well as the emulation of a particular style of film-making – what we might call Vietnam Verite, ‘Platoon (1986) also painstakingly ‘re-enacts’ a number of key photographs of the war including the burning of houses with Zippo lighters at Cam Ne, a Vietcong suspect shot in the head during the Tet Offensive and the murder of civilians by US troops at My Lai” Westwell. G. pg 78) (8)

It is argued by Marita Sturken (9) that this ‘re-enactment’ is a way of coming to terms with previously traumatised cultural imagination.

‘Hollywood movies like ‘Platoon’ deliberately restage these iconic photographs, blurring the boundaries between re enactment and original event and establishing a more concrete historical significance…significantly this mechanism enables the film to consolidate processes of cultural revision already put in play by the cycle of Vietnam War movies released in the early 1980’s’(Westwell. G. pg 79) (10)

In my interview with Philip Castle, (11) a British illustrator who designed the poster for ‘Full Metal Jacket’ he showed me an alternative design for the poster that he was commissioned to make but was never used. We had the following exchange:

PC: Have you seen that before?

SM: Never

PC: So there’s no reproduction in the Archive? (The Stanley Kubrick Archive, based at London College of Communication)

SM: No, I’ve never seen that before. It’s wonderful to discover because this (the helmet) is such an iconic image for ‘Full Metal Jacket’ it’s very unusual to see something like that.

PC: I think that some of us had in mind that for certain regions the helmet might be too provocative.

I also found in the Stanley Kubrick archive a fax transcript to Stanley Kubrick – sender unknown but probably Julian Senior – Vice President of Publicity at Warner Bros.

Fax 25th Feb 1988 – “Firstly and most urgently – in order to maintain the same identity with our posters and newspaper layouts they wish to secure the ‘cowboy’ art to reproduce the record jackets as opposed to staying with the current ‘helmet’ campaign. Obviously current stock in Japan carries the helmet campaign but with all replacement stock they would want to bring in the ‘cowboy look’…Can you let them have your approval, Stanley, so that I can advise them directly – and if same meets with your approval I will ask them to forward them the necessary art.’

These two pieces of information confirm each other, it would seem that the ‘provocative’ elements of the Graphic and the Photographic could be as powerful as the Filmic. The design for Full Metal Jacket is a masterpiece in simplicity, and clearly states the films intent, that this is a war film, that this is a war film about Vietnam is explained by the strapline that the studio had put underneath Castles design, but for me the real strapline is the inclusion of the ‘Born to Kill’ text and Peace Symbol (badge) upon the helmets surface. This alludes to the ‘duality of war’ that Joker speaks of in the film, while also providing (possibly intentionally) a subtle but memorable extra ‘strapline’ for the film. The actual strapline reads, “In Vietnam the wind doesn’t blow, it sucks”, however the words “Born to Kill” and the appearance of the peace symbol are the triggers for my memory of the poster.

Philip Castle tells me that Kubrick already knew he wanted to use a helmet for the poster, and that never changed. It is typical of Kubrick that he covered almost every aspect of his film-making, securing each detail, pinning it down to suit his vision, creating a complex, experiential film and not afraid to propose that a slice of Jungian discourse surrounding the ‘Duality of Man’ be created as an image that would become an icon of poster art. A suitable icon of promotion for the film in that its simultaneous simplicity of design hides a wealth of complexity and allowed, at the time, for a fresh and intelligent ‘cultural imagining’ of the Vietnam War.

Bibliography

1. 2. 4. 5. 8. 10: Westwell, G (2006) ‘War Cinema – ‘Hollywood on the Frontline’. Wallflower Press ISBN 1 904764 54 1

3: Herr. M. ‘Dispatches’ Picador; 14 edition (25 Oct 1991)

6: Eberwein. R. (2005) ‘The War Film’ RutgersUniversity Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey and London

7: Ronald L. Haeberle http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ronald_L._Haeberle (accessed Tuesday 23rd August 2011)

9: Sturken. M. (1997) ‘Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, The AIDS Epidemic and the Politics of Remembering’ Berkeley CA. University of California Press.

11: Steve Mepsted Interview with Philip Castle ‘On Full Metal Jacket’ http://youtu.be/TN6CqTxPROQ accessed Tuesday 23rd August 2011

Filmography

‘Full Metal Jacket’ (Stanley Kubrick, 1987, US)

‘Hearts of the World’ (D.W Griffiths, 1918, US)

‘The Wild Bunch’ (Sam Peckinpah, 1969, US)

‘Little Big Man’ (Arthur Penn, 1970, US)

‘Soldier Blue’ (Ralph Nelson, 1970, US)

‘The Blue Max’ (John Guillermin, 1966, US)

‘Darling Lili’ (Blake Edwards, 1970, US)

‘The Dirty Dozen’ (Robert Aldrich, 1967, US)

‘The Devils Brigade’ (Andrew V. McClagen, 1968, US)

‘Kelly’s Heroes’ (Brian G. Hutton, 1970, US)

‘The Boys in Company C’ (Sydney J. Furie, 1977, US)

‘Go tell the Spartans’ (Ted Post, 1978, US)

‘The Deer Hunter’ (Michael Cimino, 1978, US)

‘Apocalypse Now’ (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979, US)

‘Platoon’ (Oliver Stone, 1986, US)

‘First Blood’ (Ted Kotcheff, 1982, US)

‘Rambo: First Blood II’ (George Pan Cosmatos, 1985, US)

‘Rambo III’ (Peter MacDonald, 1988, US)