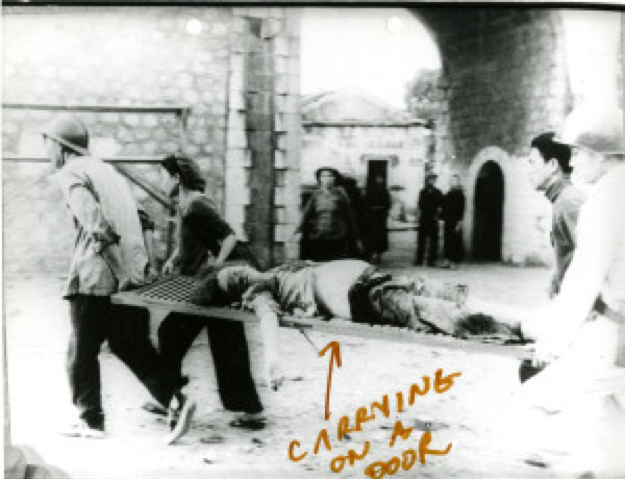

Their First Murder – New York City, October 9, 1941

“A woman relative cried…but neighborhood dead-end kids enjoyed the show when a small-time racketeer was shot and killed,” wrote Weegee in the caption accompanying this startling photograph in his 1945 publication Naked City. On the facing page Weegee showed the bloody body lying in the street.

At the International Center of Photography

near Times Square to see a retrospective exhibition of Weegee’s work. Although the title of the show is “Murder is my Business” I find there is much more to him than the bloodied corpses he would photograph after chasing the police radio messages. His van doubled as his darkroom and Weegee would photograph and print ‘on the run’ His work therefore would be first to hit the newspapers. It could be argued that he ‘invented’ photojournalism.

More interesting than the dead gangsters and hapless car accident victims, are the photographs that resulted from his scouting of the scene as he arrived; before the other press photographers and often before the police themselves.

I imagine him stepping over the body itself looking for the best angle to show the trickle or pool of blood as it leaks into the gutter. His keen eye for an environmental photograph resulted in some fascinating portrayals of onlookers, bystanders and witnesses and one photograph, “Their First Murder”, shows a group of school children who just happen to be exiting classes for the day. Weegee turns his camera on their reaction to the scene in front of them. Each child’s face is variously contorted: a woman faints in the centre of the frame and a boy laughs out loud throwing his head back (I think he’s laughing – it’s one of those sounds you can get from a photo sometimes) one girl carries an expression of horror mixed with what seems to me a kind of pleasure… she looks flushed, despite the black and white print… her gaze is greedy and keening. Another girl slightly blurred in the left foreground seems to be in a trance, looking at us and through the camera; she seems to be asking a question.

On the main floor of the Institute is a small exhibition called ‘A Short History of Photography’ which has some real gems on show and one of my favourites, ‘Miroslav Tichy’, whom I had seen in a larger exhibition at the ICP the last time I visited New York.

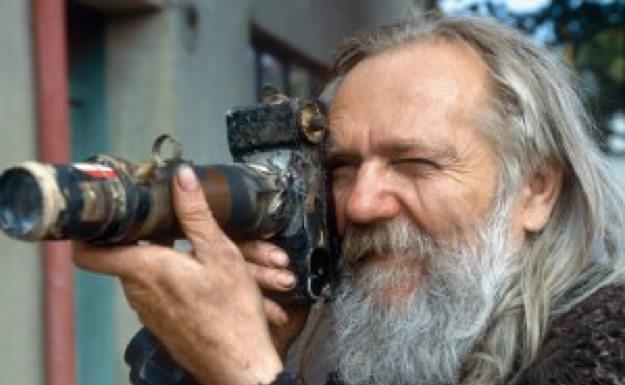

Miroslav Tichy with camera

Miroslav Tichy is a real original, and his personal story is a fascinating one. An ‘Anti–Photographer’ making his own cameras from cardboard, tin cans and using old bottle bottoms for lenses – polished up with toothpaste. In the community in which he lived he was considered unusual in the extreme, he walked the streets wearing an dark tattered coat. No one believed that his cameras worked, that he was recording actual pictures. He had the luxury of being ignored.

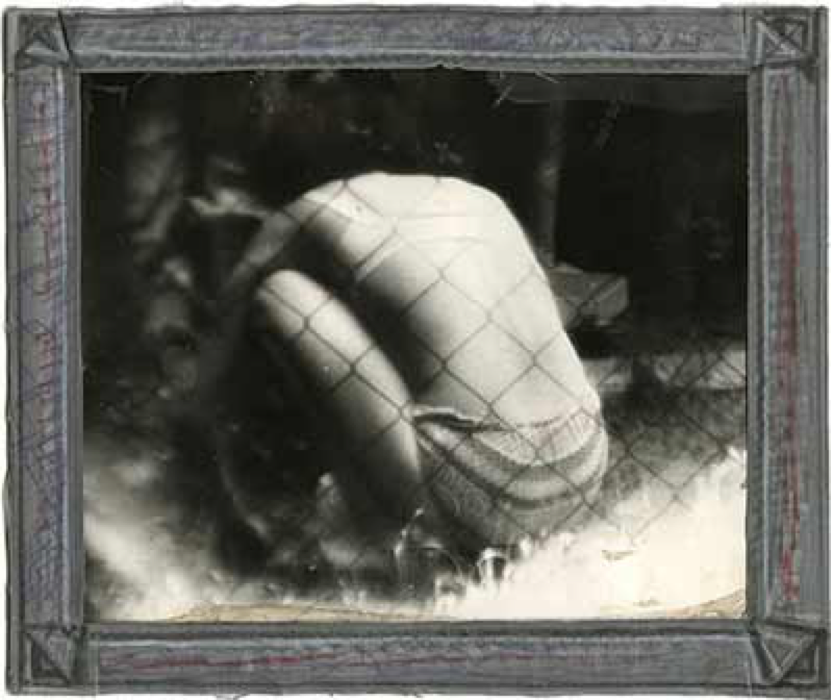

His images hastily printed on cheap photographic paper are out of focus, mysterious enigmas.

Often featuring young women and girl’s limbs, resting or walking. He would also draw on top of his work; to reinforce aspects of line and define certain areas. The works are undeniably the work of a voyeur – often shot from vantage points; hidden behind structures like fences and usually at a distance, one gets the sense that this man is sexually and sensually charged.

Miroslav Tichy – Untitled

A display cabinet of various cameras he made provided a real insight as to just how primitive a thing a camera can be. Merely a box made as light-tight as possible, a hole to let some light in and some sensitive material to record the image.

Tichy’s hand-made camera variations on this theme are mutant objects, homemade sculpture, the kind of camera we will all be using in a post-nuclear landscape. In a world finally returned to an analogue state.

It is refreshing to see Tichy’s foggy, sensual pictures against the glossy, pin sharp glamour of much photography in the show. Clarity and sharpness in a picture is sometimes like a blade held to the throat of the viewer and at those times it seems there is no way in, no forward deepening movement can be made and no possible communion with the mysterious stuff that can float behind the surface. Tichy’s photographs however feel like welcoming portals to another world, a door to what can be seen behind. They are the opposite of the taut, glossy and inpenetrable membrane. It is the blurry, crappy ‘anti-technique’ that allows this to happen: while eschewing the technology of the modern camera and the ‘rules’ of printing, Tichy’s peculiar character and the obsessive practice of his ‘bad’ photography has gained a contemporary glamour and perhaps resonates with those (like me) caught up in the exhausting pitch and chatter surrounding endless kit upgrades, digital techniques and ‘how to’ articles in magazines.