Duncan Hooson on the steps at Execution Dock, Wapping.

On a sunny day in August 2021 I met with Duncan Hooson at the Captain Kidd pub in Wapping overlooking the Thames to talk about his personal connections with the river and the importance of social engagement as an artist through his teaching and his work with ‘Clayground Collective’

“The river holds knowledge, and one has to find a way of searching, to find answers to whatever one’s interests are at the time.”

How did you inherit the River?

In 1987 I moved to something called Southbank Craft Centre which was based under Hungerford Bridge and it was part of the Royal Festival Hall and set up by the then outgoing GLC, this was under Ken Livingstone who opened up the Royal Festival Hall Foyers, because before that initiative you could only go into the Royal Festival Hall if you had a ticket to a concert. He put in place the opening up of the Hall and the opportunity for an arts centre along the front there.

I was given the opportunity of a free studio in the Southbank Craft Centre where you were on show to the public from 10 – 2pm then you could close or keep working, so that was why it was free; you were imparting information about your practice to the public and it got me quickly into that thinking; rather than being an isolated artist I would talk about my work and interests with others. So for me – when the studio was closed and because of where I was located I would often straight afterwards go for a walk along the beach, depending on time and tides. That was from day one – this beach opened up to me which became a place of discovery, a place to see the city very differently – being below the city gave me a very different perspective on the place, that for me became a real thinking space. I could get out of the workshop which was very busy, there were 20 different artists, craftspeople and theatre makers so it was often a noisy environment. For me the beach was the one place I could escape the noise of the city and enjoy that sound that everybody loves; the lapping of the water.

What I started to collect were things that you might do as a beachcomber, with not any great interest in treasure, but just gathering things of visual interest, and coming to understand the history of place, it was only later that I understood that objects on the foreshore tend to stay close to the spot they went into the river, but I was getting a sense of just what you could happen upon along this stretch of beach, that things were only visible for an hour or two and then gone. That was a really lasting impression that kept me going back on a daily basis. I became intrigued in how time and the quality of the river changed the quality of objects – particularly metal. So I started to make showcases to hold objects I found. I had gone to the Crafts Centre as a Ceramic Maker but I got interested in the possibility of presenting found objects and the creative act was making the showcases and boxes to pop the objects in, so the inspiration, or distraction, came from the river and then became my materials.

One of the first things I made in relation to time spent on the foreshore was called ‘Lost Soles of The Thames’ so I made this box; almost like a safe, that could have been made from wood from the river but actually it came from local skips. I had been collecting the soles of shoes from the beach, these were leather shoes that might have been walking the streets in Victorian times. I made this piece of work and presented it in the Royal Festival Hall as part of a show. So for me that notion of ‘the recycled’ and using recycled materials became very important to me; making strange connections between objects; not knowing the meaning of them but setting up different narratives by placing one thing next to another. I did an autobiographical piece called ‘From the Trent to the Thames’ and that was picking up odd ‘sherds’ from the beach, at that time I called them ‘shards’ (explanation of ‘sherd’ I found bits from Stoke and also from London so I made this piece of work again for the Royal Festival Hall. That whole scene was an extraordinary opportunity, like a one-stop shop; my studio was there; my gallery was there; the workspace was there and all I had to do was piece these things together. It was five years of absolute joy.

In the 1980’s London was a broken city – it was very different then. I’d see how far I could walk – often I’d get up to the Borough area before I’d have to get out. Just outside where Gabriel’s Wharf was beginning to happen there was this beach, and I was transported back to childhood and the beachcombing instinct. It would remind me of visiting Blackpool as a kid. I was always very much gathering and not interested in the financial value of something. So for me I inherited the river by luck – by being given this opportunity with the studio and then working with the Education Team at the Royal Festival Hall and using the sense of education in the work. In the 80’s people were starting to look at recycling, objects and tools. We think it’s a new thing, but it was quite a big movement back then. That was thanks to Claire West who was a curator at the Royal Festival Hall.

What keeps bringing you back to the River?

For me it’s the interest in the materials – the pottery sherds – and the history of London, finding answers in the river. As one changes and one’s interests develop it is wonderful how the river offers solutions and answers. It’s always there, always coming and going, the natural flow, which is really a flow of information, like a knowledge-exchange, the river holds knowledge, and one has to find a way of searching to find answers to whatever one’s interests are at the time.

I’ve become much more interested in history recently – particularly Roman history, you can find Samian Ware and Terra Sigillata pieces which are often overlooked because they are terracotta. One of the most memorable things was finding a roof tile and being told this was probably a tile from the Great Fire of 1666. To understand and sense that history from just one sherd I think is extraordinary. I love that the foreshore is publicly accessible, London is seen as a very expensive place, but the beach is free and there for everyone. I’m a Reader in ‘Socially Engaged Ceramics’ and this free resource is important. The value of the mementos you might find is often nothing, but it somehow becomes treasure in the imagination.

Do you have a moment or memory of time on the river that you particularly treasure?

Yes, I was at school in Stoke in a bog-standard comprehensive where you could leave at Easter without taking any exams, CSE’s as they were back then. Recently the BBC have run a series about teachers who have made a difference in one’s life and for me that person was Ken Sawyer who was the English teacher at my school. He used to drink in the pub that my Dad drank in on a Sunday so I’d see him out of school in the pub and got to know him socially as well as in school. He was a hard bastard, he had to be because it was a hard school. His area of interest was in English and Drama and he cast me in a couple of plays, just as a nutter more than anything! Until I played King Herod – which was great. Once he organised a minibus and brought twelve of us thirteen-year-olds down to London to see ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’ and this was brave of him because we weren’t the best-behaved lot, I think he opened it up to those who weren’t (well behaved) as a way of getting us out of our environment; to experience something different. It was the first play I’d ever seen, certainly the first musical. We met his mate Pete Postlethwaite who was an actor and happened to be in London, so all us kids were in the pub with him! Ken was risking all sorts of things! Anyway, the river…he got us all to hop over Hungerford Footbridge because he’d parked the minibus over the other side where Jubilee Gardens is now. We’d walked over Westminster Bridge to the theatre, and then on the way back at night he got us to hop over Hungerford Bridge! I remember seeing the river at night for the first time, it was one of those incredible moments where you are hopping, you’re laughing, you’re drunk, and this magical river is there.

Now to have a studio at the other end of that bridge many years later, there’s no way I could have foreseen that. I thought I was set for a life down the pits or in the pot factory. But Ken was the teacher who took a risk on the student’s behalf, and took us on that amazing day trip, where I really took in the city for the first time and was brave enough to come down years later by myself.

I used to think that I wanted to live by the sea, Stoke-on-Trent is one of the most landlocked places in the UK but what I’ve discovered only recently is that I really enjoy watching the river covering and uncovering, and going up and down. I think I’d like to live by water that is changing and is different all the time.

Do you have a bad moment or memory of time on the river?

On one of our Clayground organised foreshore walks with (Thames Archaeologist) Mike Webber, there’s a particular corner of the wall where the tide comes in and hits it fast. Now we have a duty of care to our participants, and we need to know the tide times and the points of danger to keep everyone safe. As we were leaving to get past this pinch-point one of the participants decided to go back to fetch the bag she’d forgotten. I was shouting at her not to; telling her to just leave it, the tide was coming in fast and she got wet from the water rushing in from a passing boat. It’s a good reminder that the tide is a dangerous moving thing. If you go into the river here the currents will take you underwater and down to the Thames Barrier before you know it.

What’s been the biggest change you’ve seen in the river in your lifetime?

Well, the river does what it does and always has done. We try to control it by building embankments and barriers but for me the change is what’s happened visually. When you’re down on the foreshore it’s the cityscape that is ever-changing. I’m critical of some of the architecture – I think it’s shit! Made by boys with computers – quite literally, I think. I hope as the layers of the city grow a lot of those profiles will be hidden – some of them are astonishing though. I still find it fascinating to be down below the city looking up and realise how big it all is. I still haven’t been to the source of the river, so that’s on my wish list. I need to go and see where it starts because I’ve seen so much of one section of it. But you know just going down to places like Faversham and the marshes and even places like Leigh on Sea and suddenly the Thames we always think of as the city becomes very different.

There’s certainly a change in the housing. Houses that now back onto the river were once working warehouses. What backs on to the river tells a story of the gentrification of London. It used to be the backs of buildings that face the Thames, the Savoy Hotel for example, that’s the back of the hotel overlooking the river. And in these wharves and warehouses it was the poor that overlooked the river from the back of the buildings, and now it’s the reversal: the most desirable residences all face and overlook the river. That’s happened in my lifetime; being in London for 35 odd years. But it is terrific that they are renovating the warehouses and not knocking them all down. Down in Wapping and Shadwell in the early 80’s a lot of artists had studios down here because it was cheap, and now…it’s completely different.

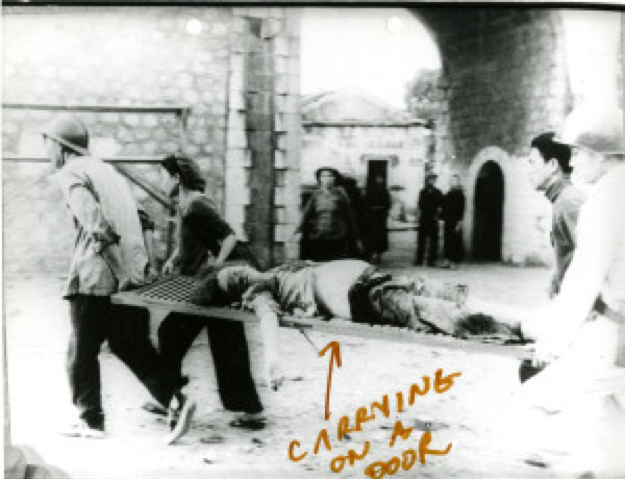

We’re here today in the ‘Captain Kidd’ pub and near the ‘Town of Ramsgate’ pub which has an alley running next to it down to ‘Execution Dock’. That alley takes me back to a different time and place, that one little alleyway. I seem to seek out anywhere in London that can take me back and that helps me imagine what it was like as a real working river and docks.

What would you like to pass on to future generations?

One of our Clayground projects, called ‘Delftware Doodles’, came from some research Claire (West) made where she found lots of Bisqueware upon which the apprentices practiced their brush skills before they were allowed to apply them to expensive tin glaze. As I mentioned earlier, I’m a reader in ‘Socially Engaged Ceramics’, so by searching through the papers that the archaeologists put together, we came up with this idea of ‘Doodles’. I like it when things like this throw up ideas where one can engage others. The idea of social engagement is important – I would hope that Clayground has helped introduce Londoners to the river again; that through our five or six foreshore walks every year over the last ten years, we have introduced the river to a whole new generation. So for me it’s about having an authentic voice about something – understanding one’s own motivation for doing projects – what I’d love to pass on is a way for other people to come up with projects and share knowledge that people can engage with and that they can pass on. These things take time and energy to put together so it has to come from an authentic discovery and love (of the river) but it becomes meaningful when people keep coming back or do something else with their discoveries so that other people learn from them. I think Mike (Webber) is great with that; he’s good with experiential learning, being able to touch objects and link them to oneself in some way, it’s great when you see young children doing that. If we are going to keep things, we need to understand the importance of them. Even just having the Thames Path is great – once you couldn’t have access to it. It’s important that developers know that in their proposals they can’t just buy and sell off large chunks of riverfront, like you have here when you’re forced to come off the riverfront and walk round buildings to come back on it. We now have this legal requirement whereby if builders are digging a trench and find something they must let people know about it.

It’s the sedimentary layers – all the beds of time laid down and discovered that keeps London interesting. Seeing the tide uncover sections of the old piers and jetties which really tell you about what happened there. So how do we share all those narratives – and give people the tools to do so? That’s what I’d like to pass on to future generations.

Is there anything else you’d like to say?

Well as I said I’ve recently become interested in Roman history. I have become more interested in the history of ceramics rather than just a focus on the contemporary. I’ve become involved with the Roman Kiln in Highgate which was of course a pottery in those times, comprising 10 kilns. There are pieces from there that are found on the Thames Foreshore – ‘Highgate Ware’. They were making pots for the Legion – not import and export, they were using really good clay up there. With my ceramics educator hat on there’s so much to be said about ceramics manufacture on the Thames itself. You had Delftware pottery, the Doultons factory opposite Parliament spewing out sodium chloride through manufacturing salt glaze. If you think about it, Bazalgette and Doulton were the perfect pairing when building London’s sewers. The readily available material for the inside of the sewer pipes was this Doulton salt glaze – it was used by Bazalgette to coat the pipes; to let the sludge and shit slide along more easily, and unfortunately also overflow the sewage into the Thames, which it still can do when there’s flooding. Thankfully, It’s a remarkably clean river these days. This glazing was the height of sewer technology at the time and you can still see evidence of the salt glazed pipes on the foreshore. One of the reasons I’ve come here today is to go to the ‘Hermitage Dump’. The ‘Hermitage Pottery’ was just up the road from here. There’s an etching depicting this inlet with pottery kilns either side of it and the dump attached to the kilns was discovered a few years ago. Once it was discovered it began to disintegrate, people began to take things away from it, no treasures or anything like that – but lots of sherds which if you’re fascinated with ceramics is still a touchstone to history. It’s nearly gone now, and I want to see what’s left. There were many potteries and kilns along here; they were lining the banks – particularly the Southbank. I have no idea why that was – perhaps it was cheaper in some way, or perhaps they wanted to keep the smoke and fire of the kilns out of the City, keeping it with the other industries along the Southbank such as the tanneries, they probably wanted to keep it away from the glamourous streets on the other North Bank. We had Southwark Cathedral Kiln, and Montague Close Pottery running down to Potters Fields, the Pickled Herring Pottery, and 15th Century Delftware. It’s an interesting question: was the knowledge of Delftware manufacture imported or exported to Holland? Was it Dutch Potters who came here with their skills and in the process learned new ones to take back? This idea of a ‘knowledge exchange’ is really interesting to me. Coming from Stoke on Trent I was aware of the canal system. One from Liverpool to London and the other from Hull to Bristol. An ‘X’ which was an incredible transport network, where things could come up the river and then be transported many miles via the canals. There are lots of beautiful examples from the Pickled Herring Pottery in the V&A, not so many from the Hermitage Pottery, and there’s quite a few from Montague Close.

Duncan Hooson is a ceramic artist and educator specialising in participatory public artworks and collaboration with artists in different fields. His ceramic and art commissions include permanent installations outside the award-winning Alsop/Stormer Library in Peckham, South London, at BBC Leicester and at Hove Museum. He has designed and made large-scale temporary work for Sadler’s Wells and South Bank Centre, London. Duncan is Stage 1 Leader BA Hons Ceramic Design at Central Saint Martins. He has extensive experience of working with students of a range of ages and abilities in formal and informal education. He is Co-Author of The Workshop Guide to Ceramics (Thames and Hudson 2012) and Co-Author of Clay In Common (Triarchy Press 2018).

Clayground Collective are a company of creative practitioners who collaborate across artforms to engage the public, educators and researchers who work in a variety of locations and spaces, responding to the specific qualities of each one. They work collectively with others including: artists, ceramicists, poets, boatmen, librarians, graphic designers, photographers, film-makers, academics, musicians and archaeologists. Co-Directors Duncan Hooson, artist and educator specialising in clay, Claire West, arts and crafts professional, and Julia Rowntree, writer and researcher, run Clayground and curate projects.